“You will be someone’s ancestor. Act accordingly.”

—Amir Sulaiman

There are lines of poetry that don’t simply sound good. They arrest your attention, inspire your heart, and deepen your breath. Amir Sulaiman’s poetry has always carried that kind of weight for me, the kind that rearranges your internal compass and leaves you standing in truth. That one line is a perfect example. It reminds you that you are living inside history, whether you feel historic or not. That your choices, your discipline, your courage, your carelessness, each one is a thread that someone else will eventually inherit.

And since we’re in Black History Month, it feels like a fitting time to tell a story like this. Not because Black history belongs to February, but because February is when many of us triple down and take the opportunity to look closer.

In that spirit, we want to highlight one of those amazing humans who lived Amir’s line with uncommon clarity. This article is dedicated to those who acted accordingly.

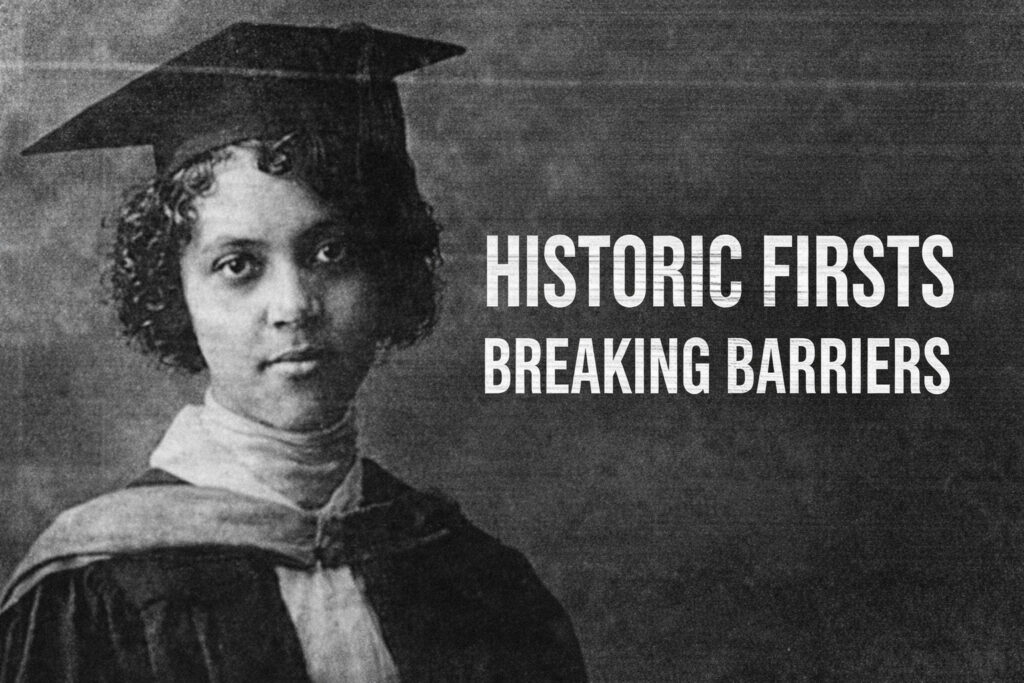

Alice Ball was only 24 years old when she solved a problem that medicine had been struggling with for generations. That detail alone is enough to make you sit up. Ball was an African American chemist in the early 1900s, born in 1892 and gone by 1916. She studied chemistry and pharmacy, and eventually earned a master’s degree at the University of Hawaiʻi, an achievement that was rare for any woman at that time, and even rarer for a Black woman. She became the first female chemistry instructor at the university. But her true legacy was not in the classroom. It was in the laboratory that she created what became the first truly effective treatment for leprosy, now more commonly called Hansen’s disease.

And oddly enough, as much as her story is rooted in early medical history, it brings to mind an unexpected encounter I once had with a creature tied to this same disease, one that scurried into my own life during a memorable stretch of time in Mississippi. Don’t worry. I’ll share that armadillo tale a bit later.

To understand what she did, you have to understand what Hansen’s disease was and what it meant. Hansen’s disease is an infectious illness caused by bacteria. It primarily affects the skin and nerves. Untreated, it can lead to numbness, injury and deformities, not because the disease “eats” flesh the way folklore suggests, but because nerve damage causes people to lose sensation and unknowingly injure themselves over time. For much of human history, the disease was treated less like an illness and more like a stain. People were cast out. Shamed. Isolated.

The name “Hansen’s disease” comes from Gerhard Armauer Hansen, the Norwegian physician who identified the bacteria behind it in 1873. Over time, the medical community began using his name partly to bring the condition into a more clinical light and partly to distance it from the fear and mythology that had followed the word “leprosy” for centuries. In places like Hawaiʻi, those diagnosed were sent to colonies such as Kalaupapa on the island of Molokaʻi, removed from their families and forced into separation, sometimes for life. It was medicine mixed with exile. Treatment mixed with punishment. And for a long time, the options were either useless or cruel.

One of the main substances doctors tried was chaulmoogra oil, extracted from the seeds of certain trees. It had shown promise. But there was a major problem. The oil was thick, sticky, and nearly impossible for the human body to absorb. Patients who swallowed it often vomited. Those who had it rubbed onto the skin got little benefit. When injected, it could cause severe reactions. In other words, the treatment existed in theory, but not in a form that truly worked.

That’s where Alice Ball stepped in.

Ball used chemistry to do what medicine could not. She developed a way to modify chaulmoogra oil so it could be injected safely and absorbed effectively. Her method transformed the oil into a form the body could actually use. The breakthrough became known as the Ball Method, and it was a game-changer. For the first time, people suffering from Hansen’s disease had a treatment that offered real hope. It didn’t just ease symptoms. It helped patients improve and, in many cases, recover. In a world where Hansen’s disease often meant exile, that mattered in ways that were not only medical, but deeply human.

Her work became the standard treatment for years, until modern antibiotics replaced it decades later. But like many stories from that era, the credit didn’t travel as cleanly as the science did. Ball’s work was so effective that it quickly became the standard, but her name didn’t always follow it at first. Over time, historians and researchers began restoring the record, and today the breakthrough is widely known as what it always was, the Ball Method.

And while her name was once quieter than her contribution, it has grown louder in our time. The University of Hawaiʻi has formally honored her legacy in public ways, including institutional recognition that places her name where it always belonged. Her story has also become a frequent reference point in medical history discussions, often cited as an example of how scientific breakthroughs can arrive through unexpected hands, and how long it can take for the full truth of a contribution to catch up to the world. In recent years, her life has even drawn interest from modern storytelling, with film and documentary discussions helping introduce her name to audiences who were never taught it.

So where does Hansen’s disease stand today? The truth is simple. Yes, people still deal with it. But not in the way most people imagine. Hansen’s disease still exists worldwide, especially in parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America. According to the World Health Organization, more than 200,000 new cases are still detected globally each year. That number is not shared here to alarm anyone, but to remind us that the world is large, and diseases do not vanish simply because they no longer occupy our everyday conversations.

In the U.S, Hansen’s disease is rare, but cases still occur. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported that roughly 150 to 200 new cases are diagnosed annually in the U.S. In other words, it is uncommon, but not extinct. And the disease is not as contagious as people assume. Most people have natural immunity. It is not something that spreads easily through casual contact. The fear attached to the old word “leprosy” has always been disproportionate to how the illness actually behaves.

Today, Hansen’s disease is treated using a combination of antibiotics called multi-drug therapy, and it is considered curable. When caught early, most people can avoid the long-term nerve damage that gave the disease its frightening reputation. Still, something about it lingers in the imagination. The stigma is stubborn. The myths are stubborn. The old fear has a way of outliving the facts.

As one medical historian put it in a recent reflection on Ball’s work, her contribution was not simply scientific; it was humane. It helped move Hansen’s disease from something people feared like a curse into something doctors could treat with clarity and consistency. That shift, the historian noted, changed the emotional temperature of the illness as much as it changed the medical outcome.

Oddly enough, I have a personal memory that makes all of this feel less like history and more like a brush with real life. In the late 1980s, before my first trip to Africa, I spent six months in Springville, Mississippi. It was one of the most enjoyable and memorable stretches of my youth. I was on a farm surrounded by nature, animals, lakes, open land and a kind of quiet you don’t get in Brooklyn. We had chickens, sheep, goats. I learned how to herd sheep during my short stint. I explored early mornings and used to catch snakes when they were semi-paralyzed by the cold. By mid-afternoon, they were completely active, mobile and ready to strike, but sealed in captivity. I caught frogs, too.

But the biggest and most amazing thing I caught in Mississippi, the day I was leaving to go back to Brooklyn, New York, was an armadillo.

If you’ve never seen one up close, it looks like a giant rat wearing armor. I scared the daylights out of my friends in the neighborhood with it. And eventually, my parents made me donate my whole little mini zoo, snakes, frogs, turtles and yes, the armadillo, to the pet store, which was probably for the best.

It’s one thing to be young and play dangerous hunter games. It’s another thing entirely to care for, feed, and maintain creatures that probably should’ve never been caught in the first place.

Here’s the part that makes that memory unexpectedly relevant. In the U.S., armadillos have been identified as one of the few animals associated with transmission of Hansen’s disease in rare cases, particularly in parts of the South. That doesn’t mean armadillos are “walking leprosy.” It doesn’t mean everyone who sees one is at risk. It simply means the disease has a few unusual pathways, and nature, like history, has a way of connecting things we never expected to connect.

And as a small historical footnote that still makes me smile in hindsight, the CDC’s Summary of Notifiable Diseases for 1988 recorded one reported case of Hansen’s disease in Mississippi that year. Thankfully, that coincidence didn’t coincide with me. But it did leave me with a quiet reminder. Even the rare things are real somewhere. Even the stories we think belong to other centuries still have footprints in our own.

And that brings us back to Alice Ball. Because her story is not just about a disease. It is about what happens when brilliance meets purpose. It is about a young woman who stepped into a scientific problem that carried both medical weight and human weight, and solved it with precision. And it is also about how legacy works. Not the loud kind. The kind that moves quietly through time, doing its work even after the hands that created it are gone.

Alice Ball acted accordingly.

And today, her name stands where it should stand, attached to the method that helped turn exile into treatment, and despair into hope.

She is one of the many proofs that the world we live in, its medicine, its science, its progress, has always carried Black fingerprints. Hers is one of the rare ones we can still trace.

And if Amir Sulaiman is right, and we will all be someone’s ancestor, then Alice Ball showed us what it looks like to act accordingly.