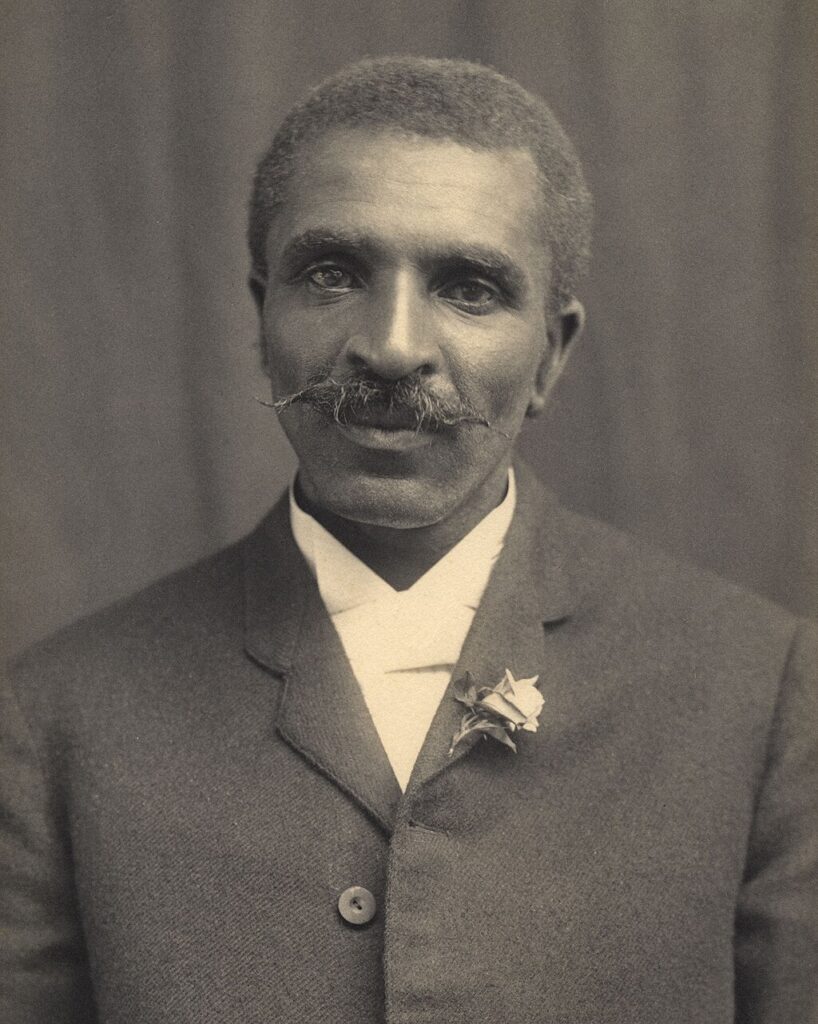

On Jan. 5, 1943, George Washington Carver, one of the most influential American scientists and educators of the early 20th century, died at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. He was believed to be 78 or 79.

Carver was an agricultural scientist and inventor best known for his work promoting crop rotation and alternative crops to cotton. These practices helped restore depleted Southern soils and improve the economic prospects of poor farmers. His research and teaching made him a national figure at a time when opportunities for Black scientists were severely limited by segregation and discrimination.

Born into slavery in the early 1860s in Diamond Grove, Missouri, Carver’s exact birth date was never recorded. As an infant, he was kidnapped by raiders and later recovered by his enslaver, Moses Carver. After the abolition of slavery in Missouri in 1865, Carver and his brother were raised by Moses and Susan Carver, who encouraged his education. He showed an early interest in plants and nature, earning a local reputation as a “plant doctor.”

Denied access to nearby public schools because of his race, Carver traveled long distances to attend schools for Black children and eventually graduated from high school in Minneapolis, Kansas. He pursued higher education despite repeated obstacles, enrolling first at Simpson College in Iowa to study art before transferring to Iowa State Agricultural College. There, he became the school’s first Black student and later its first Black faculty member. He earned a bachelor’s degree in 1894 and a master’s degree in 1896, specializing in botany and plant pathology.

That same year, Booker T. Washington invited Carver to lead the Agriculture Department at Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University. Carver remained there for 47 years. He taught generations of students and developed an agricultural experiment station that created practical solutions for small farmers. He urged growers to rotate cotton with legumes such as peanuts, cowpeas and soybeans to replenish soil nitrogen. He also promoted sweet potatoes and other crops as sources of food and income.

Carver published dozens of practical bulletins for farmers, written in plain language and often including recipes and household advice. He also created a mobile classroom, known as the Jesup wagon, to bring agricultural education directly to rural communities.

Although popularly associated with peanuts, Carver did not invent peanut butter, but he did introduce hundreds of potential uses for common crops and encourage sustainable farming practices. His work brought him national fame, including testimony before Congress in 1921 and meetings with several U.S. presidents. In 1941, Time magazine referred to him as a “Black Leonardo.”

Carver lived modestly and never married. In his final years, he donated nearly all of his savings, about $60,000, to establish the George Washington Carver Foundation to support agricultural research.

He died from complications after a fall at his home on the Tuskegee campus. He was buried beside Booker T. Washington.