Afro Brazilians enjoy the frequent translation and publication of English language texts including Audre Lorde, Ta-Neihisi Coates, Octavia Butler, and Toni Morrison. Unfortunately, publishers in the states do a disservice by not translating Afro Brazilian authors nearly enough.

There are a few important books that are available and I’ll be recommending you to add to your summer reading list.

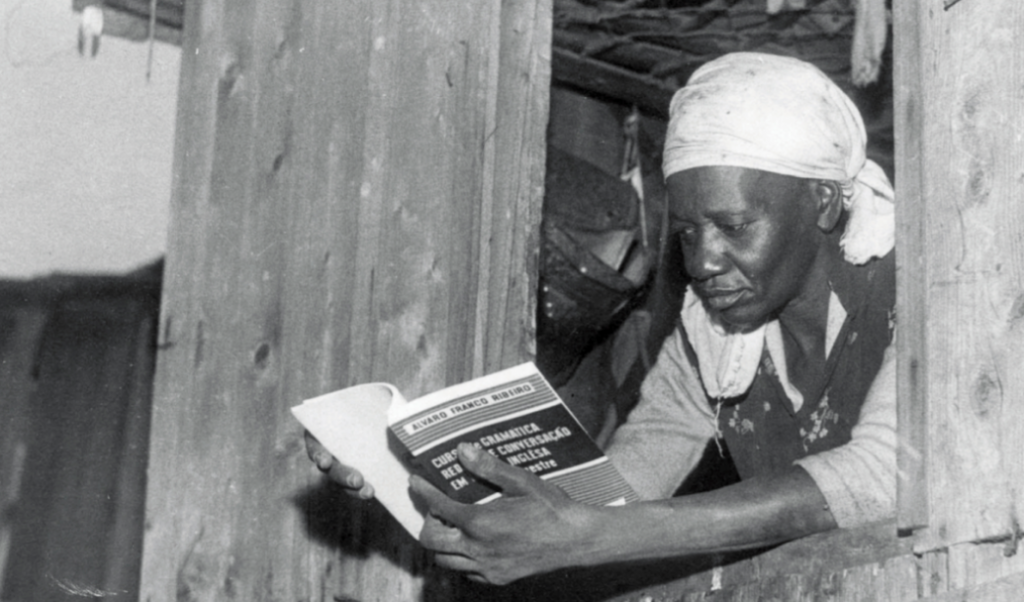

“Child of the Dark (Quarto de Despejo: Diário de uma favelada)” is by Carolina Maria de Jesus, one of Brazil’s first and most iconic writers. She was born in the southeastern state of Minas Gerais in 1913. She was only able to complete the second grade, but emerged with the ability to read and write:

“It was Wednesday, and when I left the school I saw a paper with some writing on it. It was an announcement of the local movie house. Today. Pure Blood. Tom Mix. I shouted happily- ‘I can read! I can read!’” (de Jesus, p. 9)

When she was sixteen her family moved to Sao Paulo. She worked various jobs to survive including domestic work, hospitals, and even the circus. Soon, she found herself starting a family without the help of the child’s father, a Portuguese sailor. She built a shack in the favela where she gave birth to two more children from two different men.

Life in the favela with three children was a very difficult one for Carolina. Foraging was her primary occupation. Her life was a daily search around Sao Paulo for discarded paper and other trash that could be sold. She also collected discarded food, careful not to pick anything rotten or infested. She would sell her findings each day to afford basic food and necessities for her children. She often went hungry so that they might eat.

After long days of hunting for trash, aggressively enlightening her bombastic neighbors and worrying herself sick about the welfare of her three children, Carolina applied a salve to her chaotic life as a favelada by habitually writing in her notebooks.

She would write plays, poems and stories but her life was changed in a very significant way by the writings of her personal daily journal. Her neighbors were well aware of her writings because her pen was often a sword as she would threaten to record their indiscretions in her journals:

“When the politicians had made their speeches and gone away, the grown men of the favela began fighting with the children for a place on the teeter-totters and swings. Carolina, standing in the crowd, shouted furiously: ‘If you continue mistreating these children, I’m going to put all your names in my book!’” (de Jesus p. 12)

It was this particular moment of audacity that aroused the attention of a journalist by the name of Audálio Dantas. She indulged him by allowing him to read her work and later publish segments of it in 1960 as the book “Quarto de Despejo: Diário de Uma Favelada” or in the English translation, “Child of the Dark: The Diary of Carolina Maria de Jesus.”

The book was a great success, even outselling famed author Jorge Amado in 1960. Dantas made the most of Carolina’s natural economy of words covering a five-year period of her tumultuous but mundane favela life, her daily work and family routine, shrewd political commentary, and fantastic dreams about her future. Her existential, unbending description of favela life hit the nation with a heavy dose of reality.

During the Kubitschick presidency (1956-61), Brazil was enjoying a progressive Camelot period. This golden period was a time of rapid development in cities like Sao Paulo and the new capital of Brasilia. Carolina’s book was a voice of descent surging from the discarded favelas.

Carolina’s writing is also a poignant example of self-narrative by employing her intellect against the growing force of individualism, which crushed the favelas with habitual abjection. She was able to sustain a high level of agency through self-possession, evident by her relationship with her physical and social environment. In these environments, when her physical body fails she uses her voice and the pen as a shield and sword protecting her family and carving a path into the next difficult day:

“I don’t have any physical force but my words hurt more than a sword. And the wounds don’t heal.” (de Jesus p. 49, de Jesus)

“ The good I praise, the evil I criticize. I must reserve my soft words for the workers, for the beggars, who are the slaves of misery.” (de Jesus p. 58)

“ I don’t get upset when I see a stranger looking at my dirt. I think I’ll start traveling through the streets with a sign on my back: If I am dirty it’s because I don’t have soap.” (de Jesus p. 89)

Knowing that her neighbors are illiterate, she flourishes her weapon of literacy in her personal narrative and in her social narrative to demand recognition of her self possession. But she is not just speaking to the favelas, whom she consistently separates herself from, “The only thing that does not exist in this slum is solidarity.”; she also speaks loudly to the potential witnesses outside the favela who see all poor people the same.

It’s obvious that Carolina saw her time as a precious resource. When she wasn’t searching for paper, she was ensuring her family’s survival in other ways. She lamented most of the activities of the favela. But in her narrative, she never complained about taking time to read or write. The hours she spent reading and writing allowed her to create a preferred paradigm of self-possession.

And unlike the other women in her favela, she has the ability to derive pleasure from life and is always in her own control even if escaping suffering is not. It is not dictated by having a husband of any degree of quality. She prefers to be single for several reasons, but primary among them is that having a husband would compete with her ability to read and write.

“ Where does your husband work?… don’t have a husband and I don’t want one!”

Even if her dreams of crystal palaces, beautiful dresses, and a brick house for her children were beyond her circumstance as a poor Black woman, Carolina Maria de Jesus seized the technology available to her, discarded notebooks. She used this technology along with a potent second-grade education to declare sovereignty over her own life, “I only have two years of grammar school, but I endeavor to form my character.”

Buy Child of the Dark from one of your local Black-owned bookstores and add this dynamic Afro Brazilian memoir to your summer reading.

Originally posted 2021-07-15 11:00:00.