We are adding a new feature to our Notes from the Atlantic Archives. I will be interviewing brilliant Black leaders in Brazil who you should know and hear from directly.

Dr. Barbara Carine is the founder and director of the Maria Felipa School in Salvador Bahia Brazil. The school is the first school of its kind: Black-owned and operated, centering Africana and Indigenous epistemologies. The school’s pedagogy focuses on four elements: Afrobrazil, Decoloniality, Antiracism, and Afro-centered philosophy.

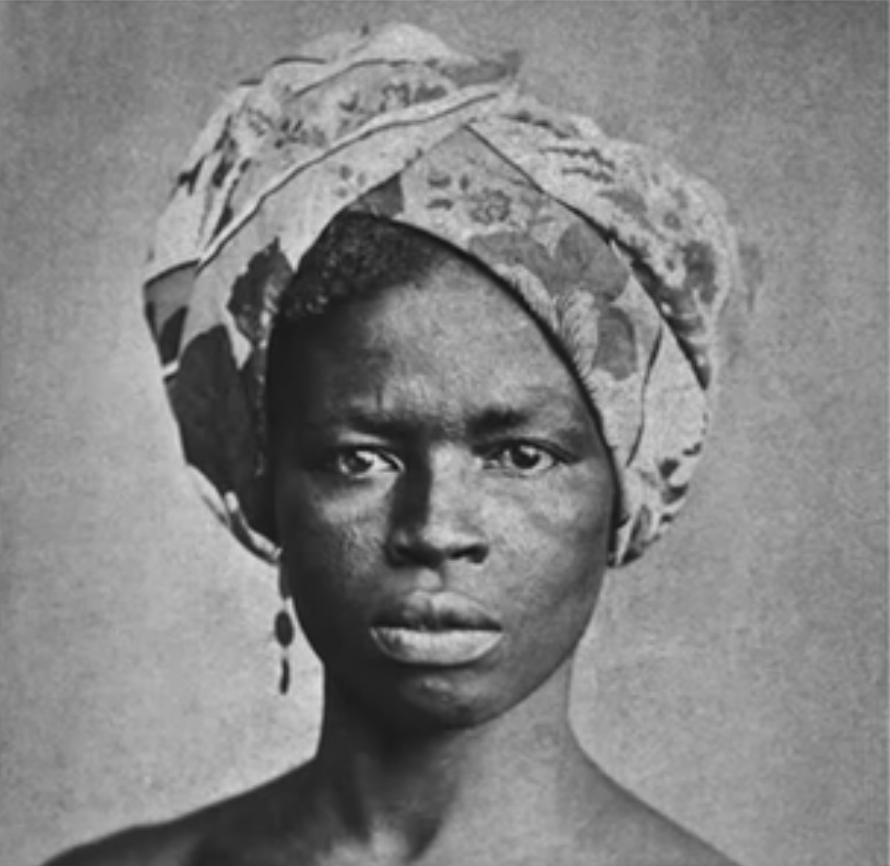

Dr. Pinheiro named The Maria Felipa School after the Black freedom fighter who led a civilian army of free and enslaved Black and Indigenous men and women to defeat the last occupying Portuguese forces.

The school’s symbol is an adorable figurine of the heroine wearing a soldier’s hat and wielding a sword.

Atlantic Archives: Welcome Barbara! Tell our readers who you are and about the work that you do…

Dr. Bárbara Carine Soares Pinheiro: My name is Bárbara Carine Soares Pinheiro, and I am a teacher, an educator, mother, businesswoman, owner of a school here in Salvador called “Escola Afro-brasileira Maria Felipa”- the first Afro Brazilian school in Brazil. I’m also an intellectual. I write from the perspective of a Black woman from Salvador, from the hood, the daughter of an ex-housemaid.

I am a chemistry professor. When choosing an educational path I was motivated by the African pioneering influence in the physical sciences, philosophy, mathematics. This helped give me purpose as a human being and a Black woman in the diaspora. My career in science helps me to empower the people around me and those who have access to my writing. I have six books published, three specifically on this topic. This year I am releasing two more, a children’s book linked to African science and another book aimed at training teachers in antiracist pedagogy.

AA: What does it mean to you to be a Black Brazilian woman?

BP: Being a Black Brazilian woman for me means having to develop skills and work harder than the average person. So my whole life has been a process to develop a strength which I did not understand well but I had to have. There are also moments of loss. I grew up fearing the loss of my father and brothers. I actually recently lost my brother to genocide in Brazil. Not by the bullet of the state but it was a result of the abandonment of Black bodies in a state that generates sadness, depression in the favelas. So I lost a 38-year-old brother who was an alcoholic for 10 years. He died at 38 of sadness, of lack of perspective of life.

AA: You have helped train our archivists on strategies for collecting and preserving precious community stories. What are some of your important memories?

BP: Wow, like …. there’s a block of memories and they represent the same thing- a free childhood in the favela. I even remember the elders complaining to us for stealing cocoa from Mrs. Marlene’s tree, stealing star fruit from Dona Helena, and riding down the hill with a shopping cart. We would play explorers in the alleys but today it is impossible because of gang wars which at that time it did not exist.

So, yeah I remember a free childhood of walking on the street shirtless, playing games, a thousand things I did that I needed to go back and forth reflecting on when I immediately entered the university at the age of 19.

AA: Why did you choose to write about Black women in the sciences and why do you think African Americans should know these references?

BP: In my graduating class of forty students, I was the only black woman. Along with my colleague Eddy, we were the only Black students in the class. I had no references of Black professionals even among the university administration. And I also did not have Black professors or teachers. This is is important to highlight because we are talking about Salvador. I did a masters and doctorate in a city with [an] 84% Black population but in spaces of power, such as the university, we did not see ourselves represented. We now know that this is because of institutional racism.

During my entire time in graduate school, I did not have any Black professors so my entire experience within the university was marked by the absence of Black women. I graduated experiencing what we call a “broken mirror logic” because although I had the credentials, I did not see myself as a scientist or a professional because I had no connections with anyone like me. There were no Black authors, especially no Black women authors. Now as a postdoctorate at the University of Sao Paulo, I have one of the very few Black professors as a supervisor, Professor Gislene Santos.

AA: This is when you decided to change things?

BP: It was important that I develop this project focusing on black women as an answer for myself first. I saw myself as a girl and then as a woman who was becoming a scientist but with few positive examples. So I said, “I will do something for the next little girl like me.” There has to be… there are… Black women out there, and they are producing science and are driving human technological development. We didn’t have knowledge about them so I began researching from an African-centered orientation. I found Black women scientists from all around the diaspora.

For me, this is not merely a job—it is a motivation for life, it’s my way of existing and living. My way of projecting a new future for my people. Not one simply marked by 400 years of slavery, but a past that begins with evidence of African intellectual power, a grand past. I believe that talking about Black women scientists is very much needed to reorient the way we view ourselves- our bodies which are constantly sexualized. We are not viewed as equal among white women or western women because we are not seen as humans. Our elder women are not respected. In the Favelas, when the police arrive they mistreat everyone, from the children to the elder women. They don’t see us as people.

AA: At Atlantic Archives, we view all of our work as potential messages for future generations. You have a beautiful baby girl. What message would you like to leave for her?

BP: I think about this often, the legacy that will I leave to my daughter for various reasons, right? I think the way we Black people learn to relate to death is very intimate, we flirt with death during our lives because we live within a state of genocide from a very early age- so we are always in this condition.

I think it’s funny that every photo of a Black woman… she sees shows empowered women and it even shocks me because they are photos of dark-skin women, of women with bodies different than mine, she sees a woman with an aesthetic, she sees a woman with strong features, she says “it’s my mother.” She always associates with her mother, so I believe this is what remains and love too. There’s also this idea that things can be different, I grew up in a family where we never said we loved each other, we don’t know what it’s like to hug one another. On birthday days we hug in a strange way, the exchanges of affection we always had were “come home, I made beans”, it was the way we said we loved each other. Until today my brother always asks “Where are you? How are things?” Sends me a message, my mother sends some herbs for me to take a bath with. It’s the ways we express love, but with my daughter, I will break that. She feels loved by me and she feels the freedom to express love as well.

The Maria Felipa School offers scholarships for families who need tuition assistance. If you would like to help a Black family with a donation, tuition is $200 per month/ $2400 per year. You can make a donation at cashapp: $atlanticarchives or paypal: @atlanticarchives.