Limited financial resources, inconsistent access to learning the game, and hardly seeing Black men on the professional tour have likely reduced the number of Black male players, Khan concluded. Now, with the arrival of the U.S. Open, where Althea Gibson broke the color barrier seventy-five years ago in 1950 and where Ashe won his first major in 1968, I offer another possibility.

Perhaps tennis’s longstanding reputation as a less-than masculine sport further deterred many generations of young Black men from taking it up.

While conducting research for my book, Serving Herself: The Life and Times of Althea Gibson, the comprehensive biography of the first Black American—male or female—to enter and win Grand Slams, I was stunned to discover how emphatically tennis was ridiculed throughout the twentieth century as a game that “real men” did not play. Some people thought that the use of the word “love” instead of “zero” had something to do with it.[1]

Others believed tennis, in comparison to sports like baseball, football, boxing and basketball, lacked enough action to be considered “manly.”[2]

The fact that women played the same sport in the same tournaments and sometimes even with men (mixed doubles) contributed to the idea that tennis was not virile.

Sportswriters and players repeatedly used one word to describe the widespread perception of tennis: “sissy.”

It’s a loaded word that judges and ridicules boys and men as not meeting traditional standards of masculinity, which valorize “physical size, strength, power, mental toughness, [and] competitiveness.”[3]

Gibson and Ashe were aware of tennis’s reputation, and both hypothesized that it explained the lack of Black boys who followed in their footsteps.

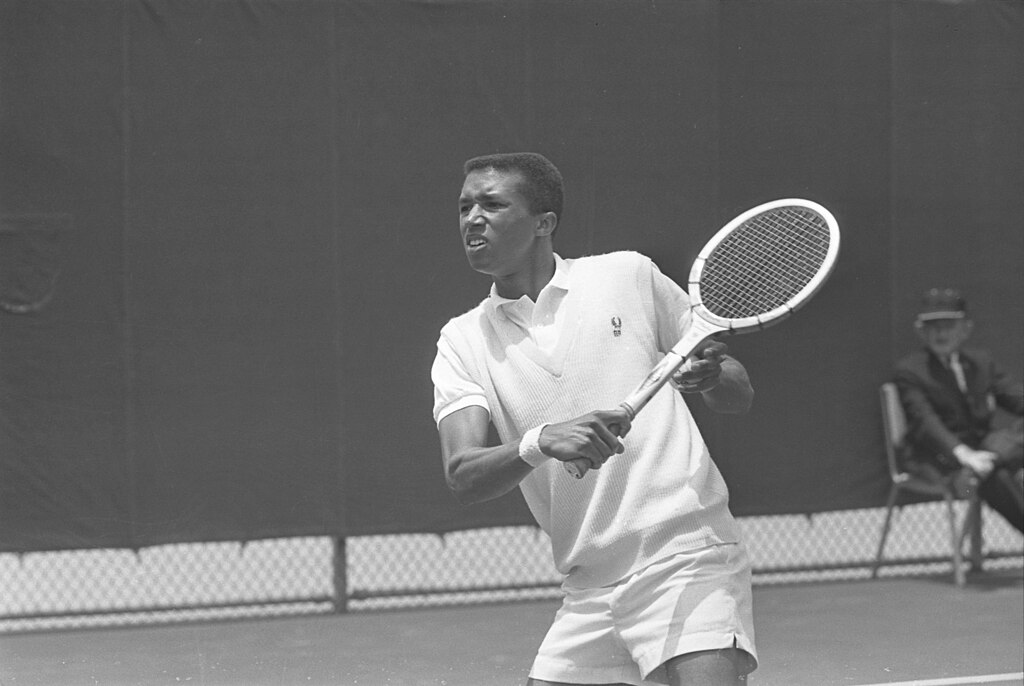

In October 1963, Ebony published an interview with Ashe to celebrate his status as the “First Negro Davis Cupper.” Ashe responded thoughtfully when asked about the “dearth of Negro talent” in elite tennis, which, until 1968, barred professionals and was exclusively for amateurs. He pointed to the expensiveness of tennis and the time required to “become proficient.” Ashe also asserted that masculinity was a factor, or deterrent.

“I would suppose that most Negroes avoid the game because they prefer contact sports and consider tennis a ‘sissy’ game,” said Ashe in an attempt to dispel this notion. “I would like to get anyone who thinks like this in a tennis game for a couple of hours under an unshaded sun and see how long they would last in this ‘sissy’ sport.”[4]

Gibson agreed. After winning her first Wimbledon singles title in 1957, she returned to the street in Harlem where she had been introduced to paddle tennis, the pickleball of yesteryear. Surrounded by local Black children who welcomed her home, Gibson shared her thoughts about tennis and young people.

“A lot of kids think tennis is a ‘sissy’ game,” she said. “I wish they wouldn’t. It’s just the thing to curtail juvenile delinquency. Tennis is as rugged as football,” she insisted. “In fact, it is the most strenuous game in the sports field.”[5]

By the 1970s and 1980s, Black men remained largely invisible in professional tennis. Lendward Simpson, Arthur Carrington, and Horace Reid played but did not become household names. By this time, Gibson and Ashe had spent years working with Black youth in inner cities and fielding questions about race and tennis.

Gibson again referred to the perceived masculinity gap when journalist Stan Hart asked her why there were so few Black tennis players. She explained that boys were turned off by the “sissy sport” label, not just expenses or the lack of tennis scholarships for college, while many Black girls worried about developing muscular bodies.[6]

Ashe echoed that sentiment in a piece in the New York Times.

“As I travel around, watching and working with young athletes, my experience has shown me that tennis is not viewed as macho enough for most black boys.”[7]

Decades later, Gibson and Ashe are still worth listening to.

Gender is a powerful device, used to set boundaries that define socially appropriate actions, behaviors, and activities.

Race is, too, and throughout American history, limited ideas about masculinity have been applied against Black men and boys.