Black Art Library, a Detroit-based library of rare books on Black artists, has transformed from a Black History Month Instagram account to a traveling exhibition—with eyes set on permanent residence in the form of a brick-and-mortar library in Michigan.

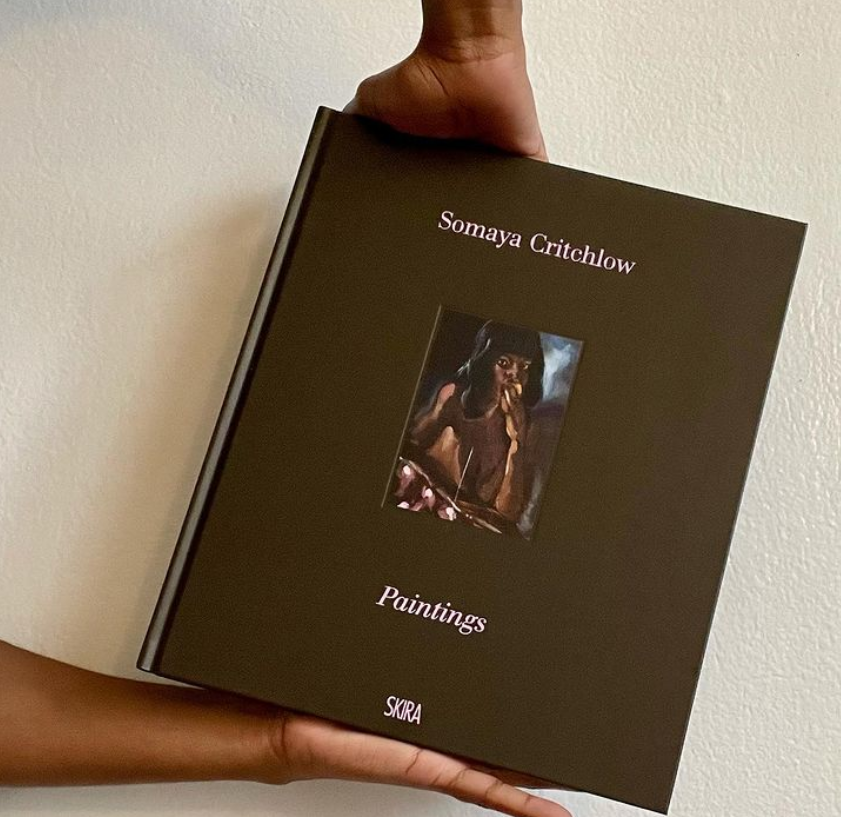

With an ever-growing archive of currently 500 books, Black Art Library is touring the country and introducing generations of unsung Black artists to museum-goers.

“I will be extremely satisfied if someone goes into this exhibition and when they leave they know the name of one more artist than they knew when they came in,” said Walton in an interview on Detroit public radio station WDET 101.9FM.

The new year will bring more exhibitions beyond Michigan, with plans to show the collection in San Antonio and Houston, Texas—her previous showing was in Cleveland, Ohio. The library’s social media presence is growing too with over 11,000 Instagram followers viewing Walton’s posts on each addition to the archive.

The collection is vast and varied with books on artists ranging from “Charles Ethan Porter: African-American Master of Still Life” by Cummings Hildegard to “Six Black Masters of American Art” by Romare Bearden and Harry Henderson, according to visual arts magazine Elephant.

Founder Asmaa Walton’s youth was spent surrounded by the art her mother worked with at Detroit Institute of Arts. But while at school in the Detroit Public School system, art classes and programs were virtually nonexistent.

Informed by her experience with lack of access to art in her schooling, Walton chose to enroll in NYU’s art politics graduate program and earned her master’s degree. From there, she secured fellowships at Toledo and Saint Louis art museums.

Before Walton fully formed the idea of a Black Art Library, she crafted daily posts on her Instagram featuring a new Black artist for every day of Black History Month, according to The Detroit News.

By early 2020, Black Art Library was born. One year later, the collection saw its first-ever exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit.

Visitors are able to physically hold and read even the hard-to-find pieces in the collection, an uncommon privilege that encourages deeper engagement with the material, Walton told Michigan State University.

“I just think we’re in a space that has to move away from these types of [white art history] canons,” said Walton in an interview with Elephant. “We have established that they erase and rewrite many histories within the arts. This project has a goal of finding as many of those lost histories as possible so I can share them with others.”