There is something almost soothing about knowing, with absolute certainty, how this country will react to Black truth in public. If you want proof that America is emotionally predictable, February will provide it every single time. You could set your watch by it: Black history appears, and suddenly a large segment of white America discovers a deep concern about racial “unity.”

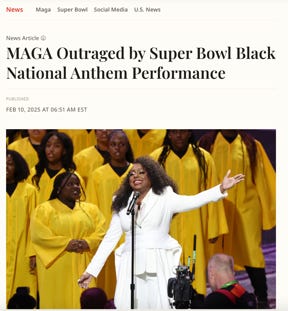

Since Sunday, the MAGA outrage machine is fuming because Coco Jones sang “Lift Every Voice and Sing” on the same football field where America sells trucks, beer, surveillance tech, and nostalgia for a country that never actually existed. Every year, the outrage over this song is framed like a spontaneous cultural eruption. But it is actually predictable and incentivized.

And this is why I love teaching media literacy because it helps us see patterns instead of reacting to the noise. And right now, in an algorithm-driven culture where outrage is monetized, pattern recognition is political power.

They MAGA machine framed the Black hymn being sung as “divisive,” recycled the “one anthem” talking point, and turned it into culture war content. That reaction fits a pattern that has repeated every single year since the NFL formalized including the song in Super Bowl programming in the early 2020s. They got mad when Alicia Keys, Sheryl Lee Ralph, Andra Day and Ledisi sang the hymn.

What matters is not that the rage happened again. What matters is why it keeps happening, and why it reliably generates outrage cycles that feel spontaneous but are actually so structurally predictable.

The annual meltdown isn’t really about the song. It’s about narrative ownership. “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is dangerous to certain political imaginations because it exists as historical evidence that Black Americans have always had a different relationship to the nation that has been defined by exclusion, resistance, and survival inside a country that demanded our loyalty while denying us full citizenship. The song is not separatist. It is testimonial. But testimonial history makes myth-based patriotism feel itchy as hell.

This year’s outrage is showing up in a moment where culture war politics are more totalizing than they were even five years ago. The ecosystem is more algorithmically sorted. The incentives to escalate rhetoric are higher. And the political backdrop of authoritarian flirtation, open hostility to DEI frameworks, and aggressive historical revisionism means these symbolic moments hit harder. So, what used to be framed as “Why do we need this?” is now more often framed as “This proves something is being taken from white people.”

You also need to consider that the Super Bowl itself is one of the last mass-shared civic stages in American culture where tens of millions of people, across ideology, race, class, and region are watching the same thing at the same time. Whoever controls symbolism in that space gets to help narrate what America is. So every pregame performance becomes bigger than itself. The field becomes a storytelling site. And for people who believe America is fundamentally a white civilizational project, a Black historical hymn on that field reads like encroachment instead of inclusion.

Then layer in the modern outrage economy. Anger is profitable. It drives engagement, fundraising, and political identity formation. So even if the number of people truly furious is relatively small, amplification makes it feel massive. Outrage becomes content and identity glue, which is political capital.

Rinse. Repeat. Next February, same script.

Another thing that’s quietly operating underneath all this is historical illiteracy. Most Americans were never taught what “Lift Every Voice and Sing” actually is. It is not a replacement or separatist anthem. It is a hymn born from Reconstruction-era Black survival and aspiration. It sits alongside American history, not outside it. But when historical literacy is low, symbolic literacy is even lower. Because so many people are not media literate, they can’t even decode what they’re seeing and hearing, so they default to threat interpretation and get pissed, even if they can’t articulate why.

Large segments of the public experience cultural moments only through algorithm-filtered commentary. They don’t watch the performance. They only watch reactions to reactions to reactions. By the time the discourse reaches them, it’s already framed as conflict. So they never encounter the song as music or history. They encounter it as controversy.

But we need to ask: Why this anthem? Why this emotional story as the national default? Most people have never read the full lyrics of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” They’ve experienced it as sound, ritual, jets, stadiums, and muscle memory. We’ve got to interrupts that autopilot and say: no Y’all, read the damn words. Look at the historical moment it came from. That’s historical literacy work, and historical literacy is dangerous to myth-based nationalism.

So let’s go ‘head and read some of the lyrics …

It opens not with unity, not with shared civic belonging, but with surveillance and battle anxiety: “O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light…” That’s a battlefield question. It’s literally asking: did we survive the night of bombardment?

Then it escalates immediately into spectacle violence: “And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air, gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.” The emotional anchor is not people. It’s not freedom. It’s not collective safety. It’s a flag surviving explosions. The nation is symbolized not by human flourishing but by a banner remaining intact during warfare.

And then you get to the verses most Americans have never been taught. The third verse reads:

“And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion

A home and a country should leave us no more?

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps’ pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

That line … “No refuge could save the hireling and slave” … sits inside a historical moment when enslaved Black people who escaped to British forces were treated as enemies. The emotional posture here is not reconciliation. It is triumph over those who sought liberation outside American control.

And then the final verse closes with conquest and divine nationalism fully fused:

“O thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand

Between their loved homes and the war’s desolation!

Blest with victory and peace, may the Heav’n rescued land

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation.

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: ‘In God is our trust.’

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

“Then conquer we must…” Not reflect. Not repair. Conquer.

Now put that anthem next to “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” which opens with: “Lift every voice and sing, till earth and heaven ring, ring with the harmonies of liberty.” Not bombs. Not survival through violence. Voices. Harmony. Liberty as something shared, not defended through explosions and death.

Then: “Stony the road we trod, bitter the chastening rod…” That is historical testimony. And then: “Yet with a steady beat, have not our weary feet come to the place for which our fathers sighed?” That is generational survival language.

And the theology is different too. “God of our weary years, God of our silent tears…” Not God who helped us defeat enemies. God who witnessed us endure.

The dominant American story is still built around innocence, inevitability, and exceptionalism. “Lift Every Voice and Sing” introduces a competing emotional truth that America is also a story of survival through state-sanctioned violence, exclusion, and forced negotiation with power. When you put those two songs side by side, you’re not just comparing music. There are two versions of American identity; conquest versus endurance, victory versus survival, domination versus collective rising.

There’s also a psychological importance here. A lot of political conflict in this country is really conflict over emotional storylines. War songs reinforce siege identity: we are under threat, we must defend, we must conquer when justified. Survival hymns reinforce collective endurance identity: we suffer, we remember, we rise together anyway.

And also, when Black women sing this song on the biggest stage in American sports, it lands as moral witness. It sounds like history speaking in a voice that was never supposed to survive long enough to sing on national TV. And for people invested in a myth of historical innocence, that can feel like indictment even when it is simply testimony.

And if we really want to keep it all the way real: “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is actually closer to what people claim they want from a national song. It is about collective rising. It is about survival without glorifying violence. And it is about striving toward liberty rather than declaring it already perfected.

And maybe that’s the real discomfort, Y’all. One song centers conquest. The other centers endurance. One says we won. The other says we survived and are still trying to become something better.

So if the country is gonna keep having this fight every freakin’ February, maybe the more honest question isn’t why the Black hymn feels political. Maybe it’s why a war survival chant has been treated as emotionally neutral for so damn long. And maybe the answer is simple: one song protects mythology. The other tells the truth.

What a nation chooses to sing together is, eventually, what it chooses to become.

Thanks for reading. If this piece resonated with you, then please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Paid subscriptions help keep my Substack unfiltered and ad free. They also help me raise money for HBCU journalism students who need laptops, DSLR cameras, tripods, mics, lights, software, travel funds for conferences and reporting trips, and food from our pantry. You can also follow me on Facebook!

We appreciate you!