White supremacy has never relied on white faces alone. That would be far too easy to dismantle. If white supremacy only moved through white bodies, it would have died a long time ago.

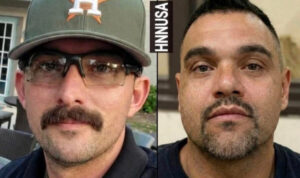

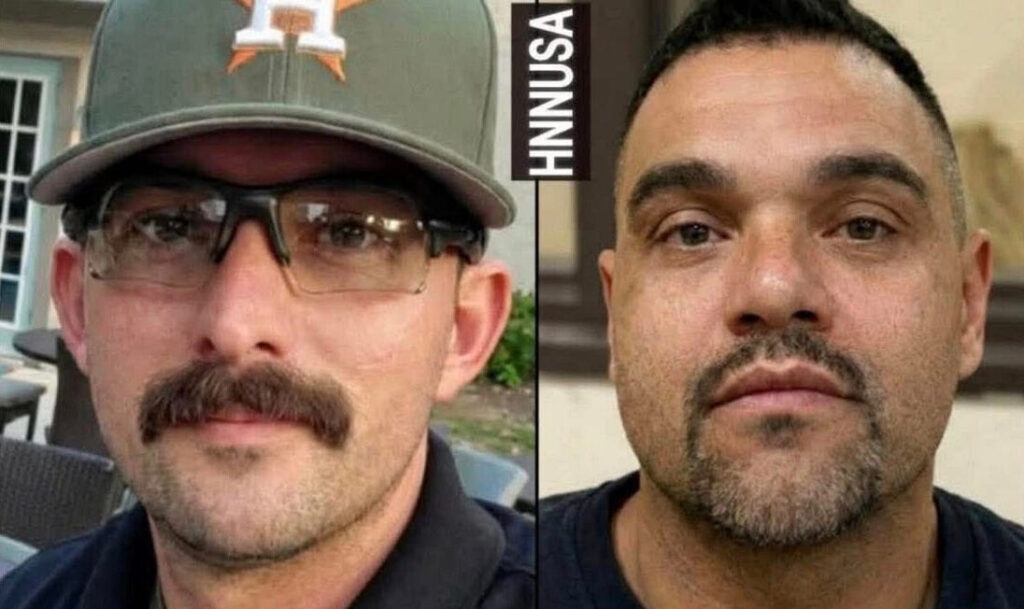

The two federal immigration agents involved in the fatal shooting of Alex Pretti last month in Minneapolis have been identified as Border Patrol agent Jesus Ochoa, 43, and Customs and Border Protection officer Raymundo Gutierrez, 35.

Notice those names.

They are not white.

Similarly, the ICE agent who fatally shot Renée Good in that same city has been identified as 43-year-old Jonathan Ross. Ross, who is white, is married to a Filipino immigrant, a fact that has drawn public attention and discussion in the aftermath of the incident.

For some observers, these facts are being offered like a defense exhibit. Like proof that racism could not possibly live there. Like intimacy is immunity. Like proximity equals innocence. Like love is somehow a firewall against ideology. But history, brutal, documented, undeniable history, tells us something much more uncomfortable. Systems of domination have never required emotional distance from the people they harm. In fact, they often thrive on intimacy with them.

And this is where people start reaching for the word “contradiction.” How could Latino agents participate in immigration terror? How could Black and Brown officers participate in state violence? How could someone married to a woman of color still move through an institution built on racial hierarchy? How could someone “love” a person of color and still participate in a system that brutalizes people who look like them?

But the truth is, this ain’t no contradiction. This is how power works when it is sophisticated, durable, and centuries old.

So, what does it mean when two Latino men and a white man married to a Filipino woman are the ones who pulled the trigger in these fatal encounters?

It means we are way past the comfort of pretending violence only moves through neat Black-white storylines or that it’s only white folks who enforce systems built to control, punish, or eliminate people those systems decide are disposable. Power has never been that simple. Once a system is built, it doesn’t just look for believers. It looks for participants. It trains them. It normalizes the mission. It rewards compliance. And it teaches people, regardless of their own background or what they look like, how to see state violence as duty, procedure or necessity.

Because white supremacy, at its most durable, is structural. It’s policy. It’s training culture. It’s who gets the benefit of the doubt and who gets treated like a threat before they even open their mouth.

And once you are inside that machinery, the system doesn’t ask who you are. It asks whether you will do what is required to keep it running. It doesn’t ask how fast you will respond when you’re told something is a threat. It asks that you respond by any means necessary. It doesn’t ask how quiet you will stay when something feels wrong. It asks that you stay quiet. It doesn’t ask how much of your own story you’re willing to set down to carry out its mission. It asks that you set it down. It doesn’t ask whether you want belonging inside the institution more than you want distance from what the institution does. It assumes you already chose.

And that’s the part people hate sitting with: white supremacy ain’t just an attitude. It’s a whole infrastructure. It’s policy manuals. It’s training scenarios. It’s promotion tracks. It’s who gets backed up, who gets investigated, and who gets memorialized. Once you step inside that cruel machine, it starts reshaping how you understand danger, authority and belonging. That’s how systems reproduce themselves. Not just through white bodies, but through anybody willing, incentivized, or conditioned to carry out the mission.

You might say, “But for a lot of those people, it’s just a job. They get a decent salary.” And that’s exactly how systems like this stay alive by packaging power and harm inside something that looks normal, stable, respectable, and necessary. White supremacy is not just a belief system. It is not just slurs and burning crosses and open hatred. It is infrastructure. It is payroll. It is pensions. It is mortgage approvals. It is medical benefits.

And systems that operate at that scale cannot survive on white bodies alone. They never have. Not in colonial regimes. Not in empires. Not in apartheid states. Not in Jim Crow America. Not in modern policing. Not in border militarization. Power that wants to last recruits. It trains. It incentivizes. It rewards compliance. It punishes deviation. It builds pathways where participation feels rational, stable and even honorable.

Because “just a job” has always been the moral camouflage of harmful systems. Yes, it’s a job. And history is full of people who did devastating things because it was “just a job.” Slave patrols were jobs. Indigenous boarding school staff were doing jobs. Jim Crow bureaucrats stamping forms were just doing jobs. People enforcing redlining maps were just doing jobs. “I was just doing my job” has been the softest language ever used to describe participation in hard violence.

Jobs are never neutral when the job itself is built to enforce inequality or harm. A paycheck doesn’t magically erase the impact of what the work does out in the world. It just explains one of the incentives that keeps the system staffed. If “it’s a job” is the end of the conversation, then no harmful system could ever be challenged because every harmful system is carried out by somebody clocking in. The real question isn’t just why individuals take these jobs. It’s why societies keep building and funding institutions and jobs that require this kind of violence to function.

White supremacy moves through institutions. And institutions move through people. All kinds of people.

And that’s where the conversation has to grow up a little. Because if we stop at “it’s just a job,” we stay trapped in talking about individual motives like comfort, money, stability and advancement instead of looking at the machinery that turns those very normal human needs into fuel for systems that produce very predictable harm.

Because the paycheck explains why someone might step inside the system. It doesn’t explain why the system is built the way it is. It doesn’t explain why certain communities keep ending up on the receiving end of force. It doesn’t explain why the outcomes look so consistent across decades, across agencies, across generations.

So the real questions we ought to be asking aren’t just about jobs or identity. They’re about function, design and survival. We need to be asking:

What does it mean when marginalized people become the public face of enforcing policies rooted in racial hierarchy?

What does an institution have to teach you to make you see violence as procedure instead of tragedy?

At what point does the badge, the paycheck, the pension or the proximity to power start outweighing community memory?

How does proximity to whiteness through marriage, class mobility, institutional belonging reshape how people see safety and threat?

What fears keep people loyal to systems that would never fully protect them?

Who benefits when we argue about the race of the person pulling the trigger instead of the system handing them the gun?

And how many times does history have to show us that systems don’t need you to love them, they just need you to do your job?

So this isn’t just about who pulled the trigger. It’s about how systems like this keep reproducing themselves, pulling people of all backgrounds into roles that maintain the same old hierarchies.

The idea that shared racial identity automatically produces solidarity is comforting, but it is historically false. Survival systems don’t run on solidarity. They run on incentives. They run on fear. They run on scarcity. They run on the promise, oftentimes false and temporary, that if you align with power, power will spare you.

For communities that have been structurally locked out of generational wealth and stable employment, federal law enforcement jobs don’t show up as abstract moral debates. They show up as health insurance. As pension security. As a guaranteed paycheck in a country where economic instability is racialized. That doesn’t make participation morally neutral. But it explains why recruitment pipelines target communities that have been economically squeezed for generations. Because when survival is on the table, systems know many people will choose stability over collective protection. Not because they are uniquely flawed. Because they are human.

And lastly, intimacy, marriage, relationships and friendships across racial lines has never been a reliable barrier to domination.

Slave owners had mixed-race children. Colonizers had families with the colonized. Segregationists employed Black domestic workers they claimed to “care about.” Lynching mobs included men who went home to Black caregivers who raised their children. Emotional proximity does not dismantle power structures. Sometimes it helps people psychologically compartmentalize them.

Love does not automatically deprogram ideology. Desire does not automatically dismantle hierarchy. Familiarity does not automatically produce moral clarity. White supremacy has always been able to coexist with emotional intimacy across racial lines because it teaches people how to separate “my person” from “those people.” It individualizes exceptions while maintaining structural contempt.

That is how somebody can love a woman of color and still believe they are protecting “law and order” from communities of color. That is how somebody can have Black or Brown grandchildren and still support policies that cage those same children. That is how somebody can claim cultural appreciation and still participate in institutional violence. Systems survive by teaching people how to emotionally isolate their personal relationships from their political behavior.

And then there is moral language. The most powerful systems don’t frame themselves as oppressive. They frame themselves as protective. Officers are told they are defending the nation. Protecting families. Upholding law. Preventing chaos. Once violence is framed as protection, people can participate in brutality while still experiencing themselves as moral.

Nobody wakes up saying, “Today I will enforce white supremacy.” They wake up saying, “I am doing my job.” “I am following protocol.” “I am protecting the country.” Systems that want to last translate harm into procedure. They translate violence into paperwork. They translate trauma into policy language.

This is why representation alone has never been liberation. A Black or Brown face in an enforcement uniform does not automatically make the system less violent. Sometimes it makes the system more durable. Because it gives the system plausible deniability. Because it fractures solidarity. Because it creates visual proof that “this can’t be racist because look at who’s enforcing it.”

White supremacy is adaptive. It recruits. It studies survival psychology. It weaponizes aspiration. It weaponizes fear of instability. It weaponizes respectability. It weaponizes the human desire to belong somewhere safe.

The deeper horror is not that white supremacy can hate bodies of color. We already know that. The deeper horror is that it can recruit them. Employ them. Reward them. Promote them. Protect them and do it conditionally while they help maintain the system.

Thanks for reading. If this piece resonated with you, then please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Paid subscriptions help keep my Substack unfiltered and ad free. They also help me raise money for HBCU journalism students who need laptops, DSLR cameras, tripods, mics, lights, software, travel funds for conferences and reporting trips, and food from our pantry. You can also follow me on Facebook!

We appreciate you!