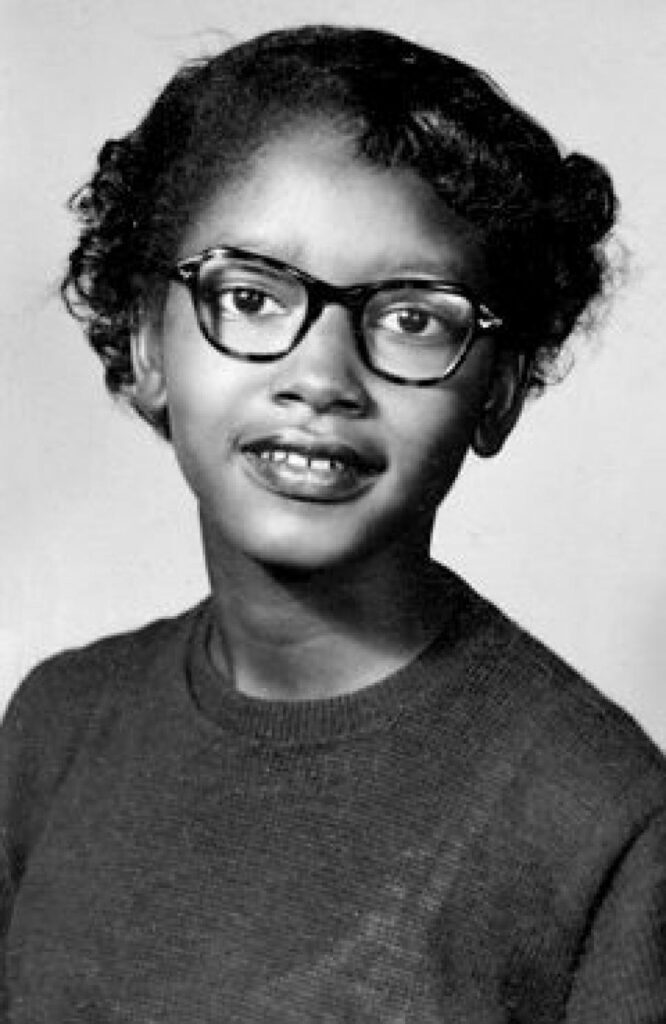

Civil rights pioneer Claudette Colvin, known for her courageous refusal to give up her bus seat to a white woman in Montgomery, Alabama, nearly ten months before Rosa Parks’ famous act of resistance, passed away on Tuesday, Jan. 13, in southeast Texas, near Houston.

She had spent many years living in the Bronx.

Ms. Colvin was 86 years old.

“It is with profound sadness that the Claudette Colvin Foundation and family announce the passing of Claudette Colvin, a beloved mother, grandmother, and civil rights pioneer,” the foundation and family announced on Facebook. “She leaves behind a legacy of courage that helped change the course of American history.”

Ms. Colvin was only a teenager when she became a star witness in a landmark anti-segregation case, which the United States Supreme Court later ruled in favor of.

On March 2, 1955, she was only 15 when she boarded a Montgomery city bus, where the harsh realities of segregation were on full display. The driver had the authority to demand that Black riders vacate their seats, particularly if they were sitting in the so-called “no man’s land” that separated the two sections. A white woman enters the bus and the driver instructs Claudette and three other Black passengers in her row to move to the back. While two complied with the order, she and another woman chose to remain seated, standing their ground. Other passengers, both white and Black, quietly expressed their disapproval of her defiance.

The last remaining Black passenger gave in. However, Ms. Colvin refused to budge.

“History had me glued to the seat,” she said to The New York Times in 2021.

Claudette’s courage didn’t emerge in a vacuum. As a student, she had been actively involved in her school’s N.A.A.C.P. Youth Council, where discussions about challenging the city’s segregation laws were already in motion. The climate of fear and oppression was palpable, especially after the recent wrongful execution of her classmate Jeremiah Reeves, who had been accused, convicted and executed for a crime he didn’t commit – the rape of a white girl he was simply dating.

The driver stopped the bus and called the police. The officers drag her, screaming, off the bus and into a police car. During the ride to the station, the two men made obscene remarks about her looks,l and one of them sat in the back with her. She was terrified that they might take her somewhere isolated and harm her.

“I didn’t know if they were crazy, if they were going to take me to a Klan meeting,” she said in an interview with The Guardian in 2000. “I started protecting my crotch. I was afraid they might rape me.”

She was charged with violating segregation laws, disturbing the peace and assaulting an officer and though convicted in juvenile court, her case became a basis for the federal lawsuit that ended bus segregation.

Ms. Colvin’s act of resistance on the bus that day was not just a spontaneous reaction; it was a culmination of her awareness and involvement in the fight against segregation. Her bravery would eventually pave the way for future civil rights actions, proving that even the youngest voices could ignite big change in the struggle for equality.

At the time, many felt that Ms. Colvin’s resistance underscored a prime opportunity for a major protest, a sentiment that echoed throughout the streets and homes of the city. Yet, in a surprising turn, local civil rights leaders opted not to elevate her as the face of this burgeoning movement.

She later expressed feelings of inadequacy, believing that her darker complexion and her economic status made her an unlikely representative for the more affluent segments of Montgomery’s Black population. In addition, rumors swirled about her personal life, with some claiming she was pregnant at the time of her arrest; however, she clarified that she actually became pregnant later that year.

This decision to wait, rather than capitalize on her bold act, reflected the complexities within the civil rights movement and the varying perceptions of leadership and representation. It highlighted the struggle of individuals like Ms. Colvin, who, despite their bravery and resolve, often found themselves sidelined in favor of more palatable figures who aligned better with the expectations of the middle class.

In December 1955, Ms. Parks would board a bus in Montgomery and make history. She was arrested, which prompted the Black community in the city to unite in a boycott of the bus system led by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., lasting for more than a year, ultimately playing a crucial role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

In 1956, Ms. Colvin was one of four Black individuals who sued the city’s bus system, led by her attorney, Fred Gray (who also represented Ms. Parks), claiming that its segregation rules violated the Constitution. Ms. Colvin was a key witness and shared her experiences from the previous year in detail.

They won the case known as Browder v. Gayle, which the Supreme Court upheld in late 1956. This ruling not only ended segregation on buses in Montgomery but also established a precedent for public transportation nationwide.

However, according to The Times, the attention surrounding the case created difficulties for Ms. Colvin. Many white individuals shunned her and even some Black community members treated her badly, perceiving her as a troublemaker.

In 1958, after having her son Raymond in March 1956, she moved to the Bronx to be closer to her sister Velma. Ms. Colvin worked as a domestic helper for a while before spending around 30 years as a nurse. During most of that time, she didn’t talk much about her consequential participation in the civil rights movement.

In a 2009 interview with The New York Times, she explained why.

“My mother told me to be quiet about what I did,” she said. “She told me: ‘Let Rosa be the one. White people aren’t going to bother Rosa – her skin is lighter than yours, and they like her.’”

It wasn’t until later Ms. Colvin started to share her own story.

“Young people think Rosa Parks just sat down on a bus and ended segregation, but that wasn’t the case at all,” she added. “Maybe by telling my story – something I was afraid to do for a long time – kids will have a better understanding about what the civil rights movement was about.”

Claudette Austin was born on September 5, 1939, in Birmingham, Alabama. When she was just a baby, her father, C.P. Austin, left the family. Her mother, Mary Jane Gadson, couldn’t take care of Claudette and her younger sister, Delphine, so she sent them to live with their great-aunt and uncle, Mary Ann (Vaughn) and Quentiss P. Colvin. Claudette later adopted their last name.

Initially, the family lived in Pine Level, a small town northwest of Montgomery, which is also where Ms. Parks spent part of her childhood. When Claudette was 8 years old, the Colvins moved to King Hill, an African-American neighborhood in Montgomery.

She is survived by her son Randy, seven grandchildren, eight great-grandchildren and her sisters Mary Ellen Russell, Joann Coretta Lawson, Theresa Diane Lovejoy Johnson, Carolyn Russell, Gloria Jean Laster and Bernice Foster Chambliss. Her older son, Raymond Colvin, passed away in 1993.

In recent years, the spotlight on Ms. Colvin’s role in civil rights has finally started to shine brighter, thanks in part to Phillip Hoose’s 2009 biography, Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice, which received the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. This recognition not only highlighted her courageous act of refusing to give up her bus seat in Montgomery, Alabama, but also educated a new generation about her decisive contributions.

Fast forward to 2019, when the city of Montgomery took a significant step by unveiling a marker to honor Ms. Colvin and her fellow plaintiffs in the landmark case Browder v. Gayle, which ultimately led to the desegregation of buses. In a further nod to justice, in 2021, a local court expunged her assault conviction, a move that acknowledges the unfair treatment she faced during her stand against racial injustice.

Thankfully, these developments reflect a growing awareness and appreciation of Ms. Colvin’s legacy. They remind us that her story is not just a footnote in history but a vital part of the ongoing struggle for civil rights.

Rest in power, Ms. Colvin.