From the moment I disembarked the Aeromexico plane in Salvador in 2011, I was swatting away the stereotypical assumptions and exchanges which greeted the late February flood of tourists.

To most, it was understandably assumed that I had traveled here to gorge on the legendary warmth of Brazilian culture and incessant passion of her colorful people. “Beleza!” (Literally: “beauty” – but slang for “All good!?”) was the expression I heard most, and often as a digressive response to my inquiries about the social and political life of Afro-Brazilians.

I was obviously coming on the scene with a way too serious attitude. I was surprised by the dogged emphasis on beauty, fun, and nonchalantness that invaded every conversation. Unbeknownst to me, I’d arrived a week before carnival. Observing this new community through the shimmer of carnival actually made it easier for me to see the equivocated performance that historically represents a deep cultural characteristic of Bahian identity, also known as “Baianidade”.

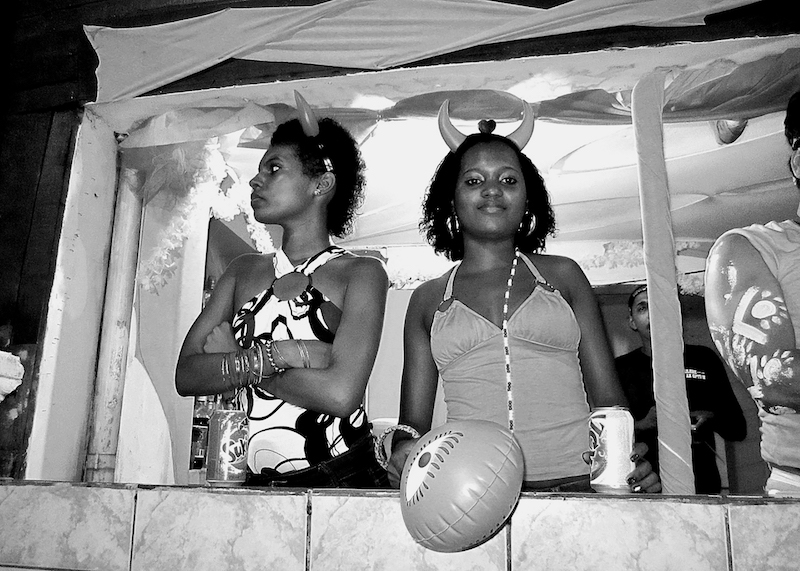

The photo above set the critical tone for me.

I snapped it during a joyous carnival procession. Two young Black women giving opposing reflections of the definitive moment. Like other stops in the diaspora, Black Brazilian identities reflect what W.E.B. Du Bois termed “double-consciousness”. In his canonical work, Souls of Black Folk, he illustrates the notion of double consciousness:

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self though the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels this twoness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, who dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. (Du Bois, 2003)

Du Bois was very clear that while specific national and political struggles of Blacks were grounded by double-consciousness, his theory was international in scope and should also be used to challenge global political systems. Critical observers of race studies in the Black diaspora naturally compare the postcolonial reality of blacks in the United States and Brazil. Like the United States, racial identity determines the likelihood of every social ill. From women experiencing abuse by health professionals to men being assaulted and murdered by the police, even when controlling for class.

For much of the 20th century, the idea of Brazil as a racial democracy was central to Brazilian racial development. The term, meant to describe modern Brazilian society as absent of a color-line, racial prejudice, or discrimination, is most often associated with arguably the most famous Brazilian, sociologist Gilberto Freyre.

According to Freyre, in his wildly popular book, Casa Grande e Senzala or The masters and the slaves (1933), modern Brazilians should be lauded as the heirs of a love story between Portuguese landlords, the meek natives and the fleshly enslaved Africans. Freyre is responsible for popularizing the concept of miscegenation (racial mixing) as the dominant trademark of Brazilian national culture.

There is, with respect to this problem of growing importance for modern peoples – the problem of miscegenation, of Europeans’ relations with black, brown, and yellow people – a distinctly, typically, characteristically Portuguese attitude… which makes of us a psychological and cultural unit founded upon one of the most significant events, perhaps one could say upon one of the most significant human solutions of a biological and at the same time social nature, of our time: social democracy through race mixture (Freyre 1933).

The concept of Brazil as a colorblind society and racial democracy has influenced generations of Brazilian citizens and the rest of the world to embrace the fantastical ideology. It paints the last country to abolish slavery (1888) as a non-racist, multiracial class society with complete equality. This fantasy dominated the first half of the 20th century creating a discourse on nationalism that held that blackness and whiteness were equally valued in Brazil.

There is far too much about race relations in Latin America to unpack within this dispatch, but the average Black American doesn’t have to search deeply for a stereotypical notion of Brazil as a mysterious but enticing cultural anomaly. Despite pandemic numbers reflecting the disproportionately higher risk and fatality from Covid for Black Brazilians compared to whites regardless of class, the notion of racial progressiveness remains a fixed, albeit decaying cliche’ in the global imagination.

The sculpture pictured below is called Monumento Mãe Preta (“Black Mother of Brazil”). It is a stone statue of a Black woman nursing a white baby.

Created in the 1920s, this iconic figure was praised as a celebration of miscegenation and a supreme maternal symbol of the triumph of abolition. Within Brazil, Mãe Preta was promoted as a symbol of family values born of selective racial mixing. Supported by both white and Black alike, Brazilians believed this to be the ideal representation of the Black woman.

For many Black Brazilians, realizing the new international stage upon which Brazil stood post-abolition, the monument represented the scrutiny from the rest of the world and pressure for Brazil to actualize its hollow promise notion of equality for everyone. For white Brazilians, Mãe Preta represented an artesian racial future fed by a beautiful African woman surrendering her agency, physical and mental, to the insatiable gullet of the white racial class.

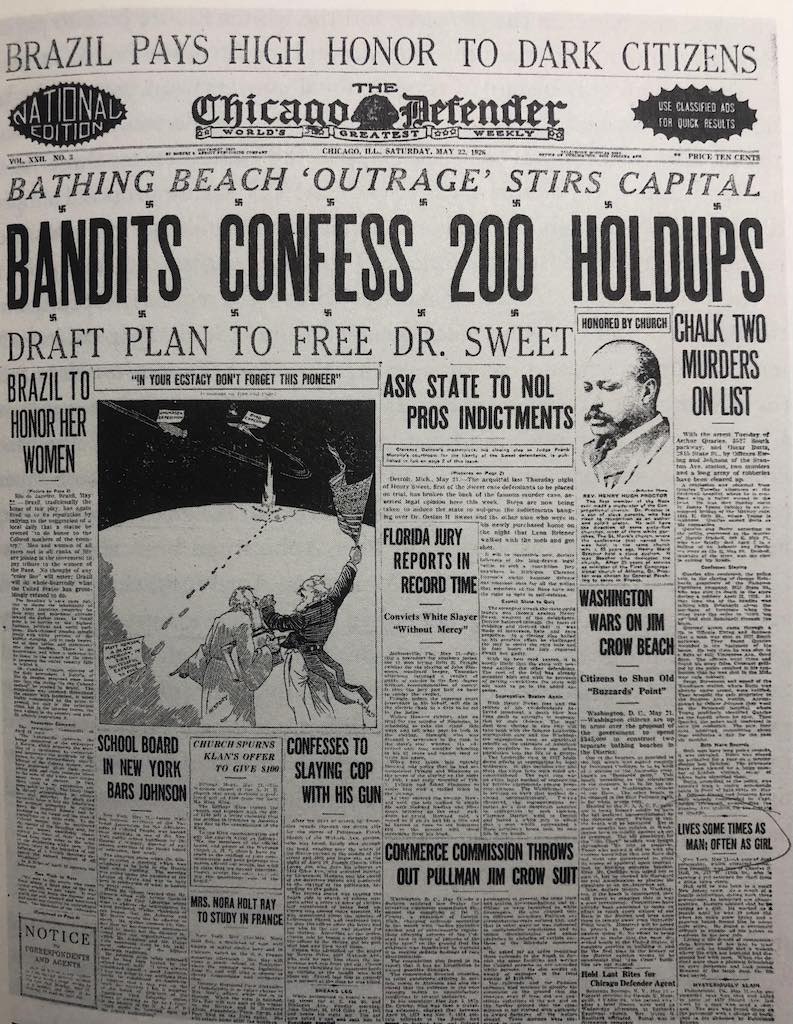

African Americans, besieged by post-reconstruction Jim Crow, saw the Brazilian myth as an opportunity to prod the United States forward by comparing her to a more attractive daughter of Europe. Although the reality of Afro Brazilians did not reflect the mythology, they too hoped that this reputation could be used as leverage, compelling the nation closer to utopia.

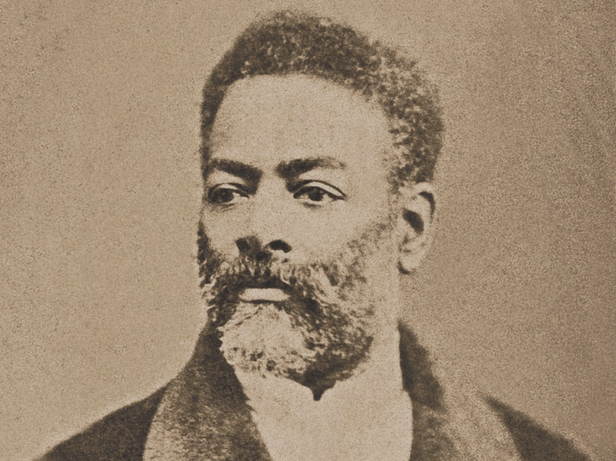

By the mid-century, the myth of racial democracy was debunked by Afro Brazilian activists but had thoroughly entranced the West. Abidas do Nascimento, Brazilian Pan African intellectual and artist, argued that this term was actually a tool for promoting whiteness.

“Another deadly tool in this scheme of immobilizing and fossilizing the vital dynamic elements of African culture can be found in its marginalization as simple folklore: a sublet form of ethnocide… an aura of subterfuge and mystification in order to mask and dilute their significance or make them seem ostensibly superficial. But despite such attempts at deceit, the fact remains that the concepts of white Western culture reign in this supposedly ecumenical culture in a country of Blacks, marginalizing and undervaluing our heritage of Africa in the process.”

This “diasporic gap”, represented a turn of the century look into the communication between Africans in the Americas and inhabits a critical conception point for understanding modern transnationalism among Black working class African descendant populations in the United States and Brazil. It is rooted in the same core issue that is the key to affectively realizing our shared destiny as African descendants in the Americas: the social condition of Black women.

The first recorded victim of Covid-19 in Rio de Janeiro (and the fifth victim in Brazil) was a Black woman.

Cleonice Gonçalves was a 63-year old domestic worker whose wealthy white employer returned from a vacation in Italy infected with the virus. The woman was tested and treated, recovering quickly, but keeping her diagnosis a secret from her maid whose services continued as normal for several days.

Four days a week, this Black woman from a poor neighborhood, slept in the servant’s room of her Patroa’s (boss/Lady of the house) plush Rio condo. For the remainder of the week, she would travel two hours away through a janky connection of packed buses to her threadbare home and her family.

The Patroa did not tell Gonçalves about her positive test or even halt her schedule while she awaited results. First Gonçalves developed bladder pain, then breathing problems and other “mysterious” symptoms. She died days later, foretelling the culling awaiting poor Black and indigenous populations continuing to this very moment in this pseudo-Shangri-la.

In 1995, Afro Brazilians were celebrating the history of Black resistance to slavery in the commemoration of Palmares, the largest maroon nation (sovereign settlements of Africans who escaped from plantations) in the history of the trans Atlantic slave movement. Palmares lasted nearly a century (1604-1694). The last decades were the most powerful under leadership of its king, Zumbi, whose death at the hands of the Dutch and Portuguese forces is the date of the commemoration which focuses on what was called “The Black Question”.

In November (Black Brazilian History Month) Black Movement activists, with the support of Leftists and the Labor movement, had a series of marches and protests– all powered by the tricentennial of the Zumbi and the Palmares Resistance.

That same year, political musician Chico César released the reggae-samba song, Mama Africa to an Afro Brazilian audience in the midst of this revolutionary moment. Radiating pop and folk vibes, the tune was an overnight and long term success. It is easily the most frequently heard song from Brazilian speakers.

Mama Africa served as an anthem not only confirming Afro Brazil’s answer to the “Black Question”, harkening the Central African spirit of Zumbi; but also a critical point of departure for the future of Black people in Brazil and in the United States: the social condition of Black women.

| Mama África A minha mãe É mãe solteira E tem que fazer mamadeira Todo dia Além de trabalhar Como empacotadeira Mama África tem Tanto o que fazer Além de cuidar neném Além de fazer denguin’ Filhinho tem que entender Mama África vai e vem Mas não se afasta de você Quando Mama sai de casa Seus filhos se olodumzam Rola o maior jazz Mama tem calo nos pés Mama precisa de paz Mama não quer brincar mais Filhinho dá um tempo É tanto contratempo No ritmo de vida de Mama | Mama Africa My mother Is a single mother And you have to make a bottle All day Besides working Bagging groceries Mama Africa has So much to do In addition to caring for baby Along with being cute Little son has to understand Mama Africa goes back and forth But will never leave you When Mama leaves the house Your children are with God Encircled in his jazz music Mama has calluses on her feet Mama needs peace Mama doesn’t want to play anymore Little son takes a break It’s so much trouble At the pace of Mama’s life |

Ceaser’s ode to Black mothers reached international ears while its protagonist’s battle for a voice from the lowest rungs in the social class. In a Fall 1995 interview with the journal Callalo, Afro Brazilian poet and social worker, Mirian Alves activates, Ceaser’s passive voice:

I know only the following: nobody is going to help me do anything. When they think they are helping me do something, they are putting me in a subjected position. I am not subjected; I am a subject. I don’t want to be an object anymore. I am tired of having to yell all the time that I am a subject when there is a truckload of rubbish pushing me to be an object. I don’t want to be subjected; I want a trade relationship in this capitalist society. I am a direct heir of the society of slavery, and that also enslaves me in a more modern way, paying for the fruit of my labor in a devalued way.

Miriam Alves, Callaloo 1995 (translated from Portuguese)

The Black feminist poetics of Alves were echoed off the deep but unhailed substructure of Black Brazilian feminism built by Lélia Gonzalez decades before the Brazilian Black Movement forced the government to guarantee access to higher education for its Black population. Gonzalez forged a way to a doctorate in political anthropology and promptly designed a radicalized feminist theory that centered the working Black women, usually domestic workers.

Researcher and biographer, Flava Rios says of Gonzalez, “She brings up the dimension of women who lived in master’s houses, of working women, of black women, as slaves, but also as domestic workers, who played a key role in forging the Brazilian national culture … She has a very important focus on the struggle against racism through people who are invisibilized in the social structure, in Brazilian culture.”

Lélia Gonzalez was born in Belo Horizonte, a southeastern town in Brazil, in 1935 to a poor family including 18 children. The second youngest child of an indigenous mother and a Black father who was a railroad worker, Gonzales achieved multiple degrees in history, philosophy, communication and anthropology. In her remarkable 59 years, she changed the political future of Brazil by co-founding Brazil’s Unified Black Movement which was responsible for the criminalization of racism in the Brazilian constitution subsequent affirmative action legislation. Gonzalez passed away from a heart attack in 1995.

“It is undeniable that feminism, as theory and practice, played a fundamental role in our struggles and achievements, in that, when presenting new questions, it not only stimulated the formation of groups and networks but also developed the search for a new way to be a woman…

“The black woman is the major focus of [social and gender] inequality in society. It is in her that these two types of inequality converge — not to mention class inequality, social inequality…”

“By reclaiming our difference as Black women, as Amefricans1, we know very well how much we bear the marks of economic exploitation and racial and sexual subordination. And this is exactly why we bear the mark of everyone’s liberation. Therefore, our motto must be: organizing now!”

In 1997, Angela Davis visited Brazil for the first time. She was expressly coming to celebrate the life of Lélia Gonzalez, whom she had first met at an academic conference at Morgan State University nearly a decade earlier. She also met the activist progeny of Gonzalez and has continued to work with multiple Black feminist groups and leaders throughout Brazil until today. Davis’s autobiography became a best seller in Brazil when the Portuguese translation was published in 2018. While at one of the dozen speaking engagements she attended, she was quoted saying,

“It’s so strange to me that you all seek me as ‘the name’ of Black feminism. Why do you all want this? You all have Lélia Gonzalez, who wrote about intersectionality long before the term was even born.”

- Amefricanidade, or Amefricanity, is a category developed by Lélia Gonzalez for conceptuation of race on a continental level, articulating the voices, forms of resistance, language, political experiences, and narratives of Black and Indigenous peoples in the Americas. “The category of amefricanity incorporates a whole historical process of immense cultural dynamics (…) that is Afrocentric,” Lélia wrote in the 1988 A categoria político-cultural de amefricanidade.