In her powerful new book, acclaimed journalist Antonia Hylton uncovers the harrowing, hidden stories of one of the last segregated asylums in America and how it connects to the country’s ongoing neglect of Black mental health.

It’s no secret the United States has a long history of weaponizing psychology to defend its dominance over Black Americans. At the core of enslavement, specifically, were the theories of white medical practitioners who argued that Black people were resistant to mental illness. From 1700 to 1840, they hypothesized that since enslaved Africans did not own property, participate in business or engage in civic matters such as holding public office or voting, they were, in fact, happy because they were not emotionally compromised by the pressures of everyday life. And due to the goodwill of their enslavers (they provided clean air and exercise by way of outdoor fieldwork), enslaved people actually enjoyed and found enslavement beneficial.

Ironically, as the number of enslaved people who attempted to escape from captivity increased, the act itself was classified as a form of mental illness called “drapetomania” a supposed psychological disorder coined by Virginia physician (and “Negro guru”) Samuel Cartwright who would prescribe “whipping the devil out of them” as a cure.

After the prohibition of slavery, the United States discovered another way to control Black minds in order to exploit more free labor: Black Americans were corralled and forced to build asylums, which they were brought into to work as indentured servants. However, the details of this critical piece of American history, one that lends itself to a warped, general perception of mental health among Black people today, remained almost entirely untold—until now.

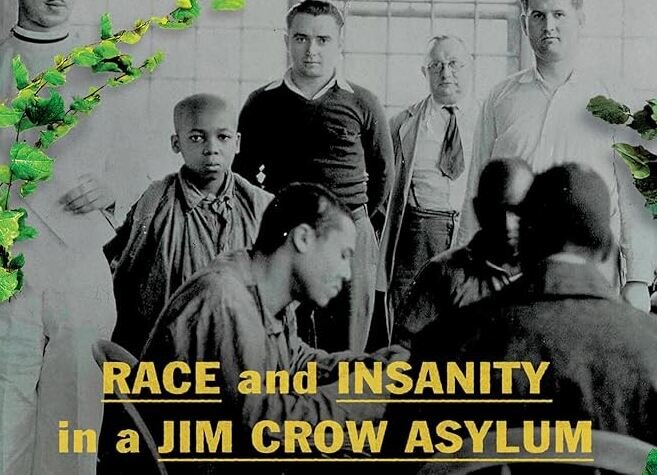

In her compelling new book, Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum, Peabody and Emmy award-winning journalist Antonia Hylton pieces together the 93-year history of Maryland’s Hospital for the Negro Insane, later named Crownsville Hospital, a segregated asylum established in 1911 in Anne Arundel County, MD, that recounts the lives of the patients who lived there. The facility was run as a segregated farm colony, fueled by the work of Black patients who were committed week after week, year after year, becoming well-known for its abuse and overcrowding. It was fully operated by the patients, as they were forced to manage everything from cleaning responsibilities to the inventory and storage of human corpses, along with cooking meals and serving white personnel.

By the middle of the 20th century, Crownsville had desegregated its patient base which allowed Black staffers to engage in restorative care for the Black patients who had long suffered without it. It also afforded them access to records that revealed how, in addition to the longstanding, blatant disregard of adequate mental health services for patients who truly required them, there were scores of Black residents who weren’t actually suffering from mental illness at all. They were simply ordered to the facility for senseless, ill-considered reasons and then marginalized for the sole intent of sustaining an increased work output that Crownsville did not want to pay for.

“This was about getting access to free Black labor,” Hylton tells NPR. “In the hospital records…what you often see was a lot more commentary about the labor and the amount of products that patients could produce than you would see about mental health care outcomes, which, I think, tells you a lot about a facility’s priority.”

For instance, Hylton details a story about a Black patient whose records were found by a Black staff member who had come to work at Crownsville in the 1960s. She discovers that the patient’s only reason for being committed to the hospital was because they inadvertently frightened a white motorist. The white driver cut them off in traffic which startled their horse. As a result, the white person felt threatened by the horse’s reaction (and by default, its owner), so the Black individual was ordered to Crownsville where they were labeled “insane” and involuntarily detained for decades.

Succumbed by the competition of an eventual rise in prisons and jails housing more of the mentally ill, Crownsville would permanently close its doors in 2004, but what Hylton shows in Madness is while there were legitimate mental health diagnoses for Black patients (and some were indeed met with sound, therapeutic treatment by practitioners who looked like them), they were all convoluted by the fact that the hospital (and so many others like it at the time) had become a vessel for any type of Black individual who was regarded as undesired and undeserving – a reflection of all the battles directly connected to civil rights amid a mental health care system that continues to uphold shame and stigma within the Black community.

When asked what we can take away from the book, Hylton stresses the importance of what the concept of “safe spaces” really means in mental health care and how, if governed fairly, can implement true awareness and a clear vision for everyone. In addition to Crownsville’s horrific accounts, Madness also highlights how the notion of a supportive environment was a critical component for those Black patients whose stories ended in healing and positivity.

“It’s not necessarily medication or a wonder drug or discovery that makes all the difference in their life,” she says. “It is a community that wraps their arms around them. It is that they actually have support, and they actually are able to recover with the full knowledge that they’ll be welcomed back somewhere, that they have a life ahead of them.”

Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum by Antonia Hylton is available at all major retailers where books are sold, including the following Black-owned bookstores: