On September 2, 1956, the small town of Clinton, Tennessee, emerged as a significant battleground in the fight for school desegregation in the United States.

Following the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, which declared segregated schools unconstitutional, a federal judge mandated that 12 Black students, known as the Clinton 12, enroll at the previously all-white Clinton High School in the fall of 1956.

The 12 original students were Jo Ann Allen, Bobby Cain, Anna Theresser Caswell, Gail Ann Epps, Minnie Ann Dickey, Ronald Gordon Hayden, William Latham, Alvah Jay McSwain, Maurice Soles, Robert Thacker, Regina Turner and Alfred Williams.

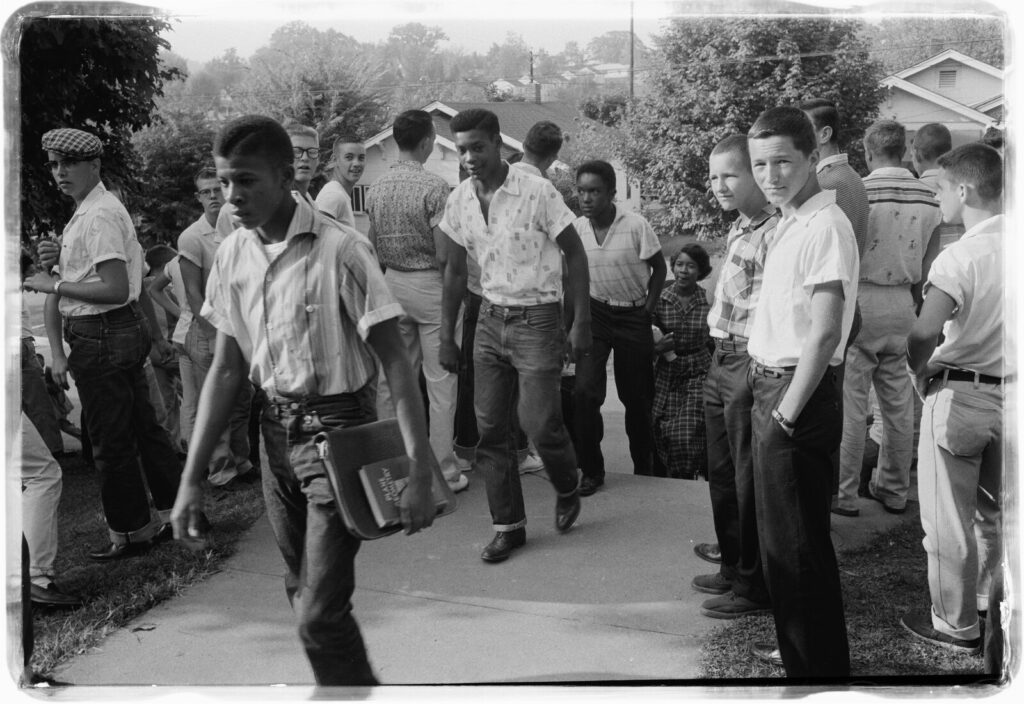

This mandate triggered a strong and deeply hostile response. Segregationist activists, some from outside the community, arrived in Clinton to incite resistance. Their inflammatory rhetoric fueled demonstrations that quickly escalated into mob violence, endangering both the students and their families.

In response to these events, Governor Frank Clement made the pivotal decision to deploy 600 Tennessee National Guardsmen to Clinton on Sept. 2. This action distinguished Tennessee as the first Southern state to utilize its own military force to uphold the Supreme Court’s desegregation order—predating the more widely publicized intervention in Little Rock, Arkansas, the following year.

The National Guard’s presence was critical. Soldiers patrolled the streets, shielded the school and physically separated the Clinton 12 from jeering crowds as they entered the building. Local ministers also provided support, accompanying the students despite threats to their own safety.

While the Guard’s deployment subdued the most immediate dangers, opposition to integration persisted. In 1958, the intensity of local resistance culminated in the bombing and destruction of Clinton High School by segregationists.

Tennessee’s decision to enforce federal law despite intense local opposition set an important precedent for other Southern states navigating desegregation.