On September 22, 1906, Atlanta descended into one of the deadliest outbreaks of racial violence in American history. Over three days, armed white mobs rampaged through the city, attacking Black men, women and children in what would come to be known as the Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906.

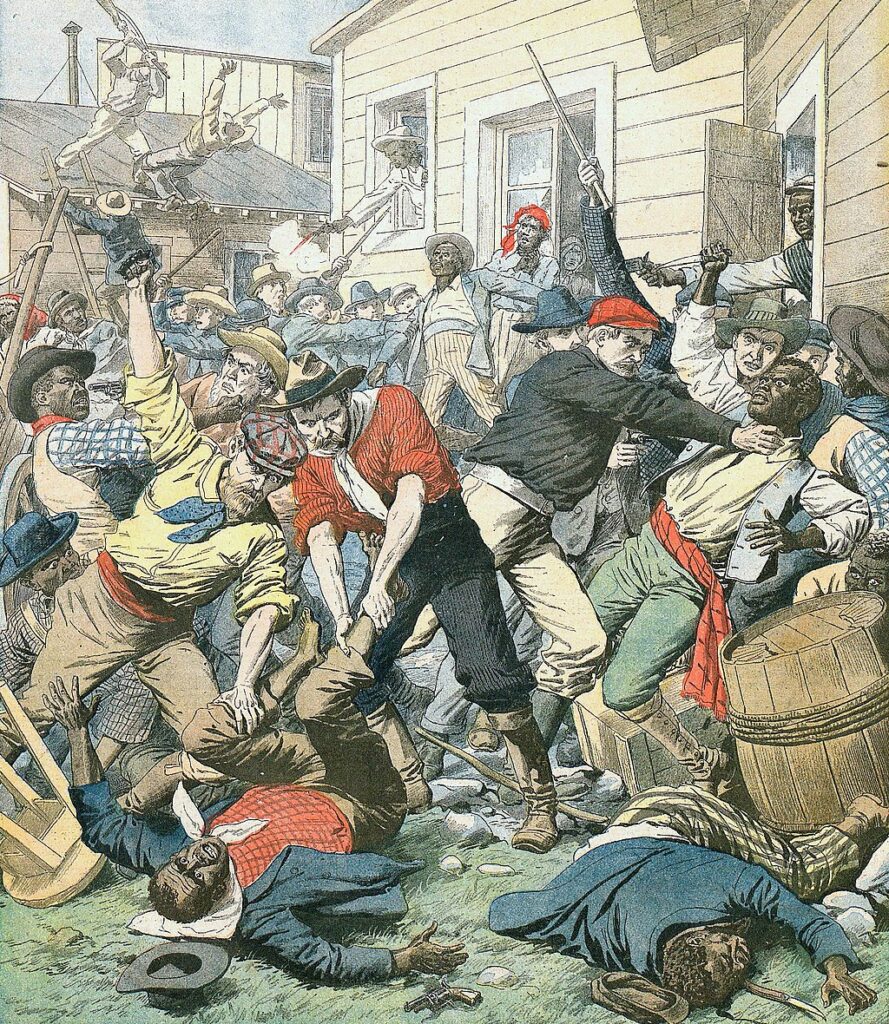

The violence was sparked by sensationalized newspaper reports alleging that Black men had raped four white women. By nightfall, mobs numbering in the thousands began pulling Black people off streetcars, beating, stabbing and lynching them. Black-owned businesses were looted, homes destroyed and entire neighborhoods terrorized.

The official death toll listed at least 25 African Americans and two whites killed, though some reports estimated the number of Black victims as high as 100. The Atlanta History Center notes that some were hung from lampposts, while others were gunned down or bludgeoned in the streets. International newspapers, from Paris to London, carried headlines describing the bloodshed as a “massacre of Negroes.”

Beneath the immediate spark lay deeper causes. Atlanta’s rapid growth after the Civil War brought waves of Black migrants seeking opportunity. By 1900, the city’s Black population had swelled to 35,000. Many carved out success despite Jim Crow oppression, most notably Alonzo Herndon, a formerly enslaved man who became one of the South’s first Black millionaires. His upscale barbershop serving white elites was among the first businesses destroyed by the mob.

White politicians took advantage of these conflicts, and Hoke Smith (the 58th governor of Georgia) and Pulitzer Prize-winning Clark Howell publicly advocated for Black voters to be denied the right to vote during the 1906 gubernatorial campaign, and their publications stoked racist unease about “Negro crime.” In this context, false reports of assaults were the catalyst for widespread violence.

Many Black residents accused police and some Guardsmen of helping the mobs, but it wasn’t until Governor Joseph M. Terrell summoned the Georgia National Guard that order was restored. Segregated neighborhoods like “Sweet Auburn,” which subsequently developed into a thriving center of Black business and culture, grew faster as a result of the massacre, which decimated Atlanta’s Black community and forced many businesses to relocate.

It was not until 2006, on its centennial, that Atlanta formally acknowledged the tragedy.