When news broke that acclaimed filmmaker Ryan Coogler had negotiated the reversion of rights to his latest film, Sinners, within 25 years, it immediately sparked headlines in both the entertainment and legal worlds. On paper, this move looks like a shrewd industry power play. After all, few filmmakers—let alone Black filmmakers—have the leverage to demand ownership terms that precede the statutory copyright termination window by a full decade.

But as Coogler revealed in an exclusive interview with Business Insider, the motivation wasn’t about money or evenpower. It was personal. Deeply personal.

“That was the only motivation,” Coogler said. “It was this specific project.”

The Personal is Political and Powerful

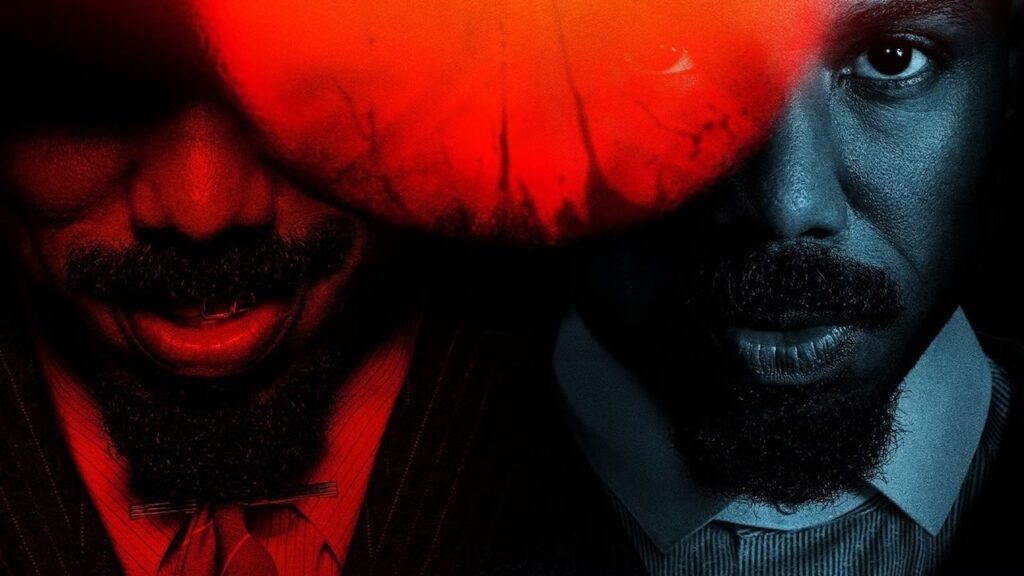

Set in the Jim Crow-era South, Sinners tells the story of twin brothers (both played by Michael B. Jordan) who take over a juke joint in 1930s Mississippi, a story steeped in themes of resistance, resilience and Black ownership. And that last word, ‘ownership’ is what turned a business deal into a cultural statement.

Inspired by his late uncle James and his grandfather, whom he never knew but who hailed from Mississippi, Coogler said the film’s period blues soundtrack, setting and familial themes made the project feel like a personal inheritance. Owning Sinners, a film about Black men reclaiming a space of joy and expression in hostile territory, became a matter of symbolic justice.

And make no mistake: symbolism backed by legally enforceable ownership rights is power. It’s also legacy.

What the Law Provides—and Where It Falls Short

Despite Coogler’s personal reasons for requiring express rights reversion in order to green-light the deal, let’s be clear about what makes the art of this deal so significant.

The U.S. Copyright Act does provide a legal path for authors to regain rights to their works—even when they’ve transferred them. Under Sections 203 and 304 of the Copyright Act, creators (or their heirs) can terminate a grant or license 35 years after it was made (or 56 to 61 years under older provisions). This termination right was designed to give authors a second bite at the apple—an economic reset if the work turns out to be far more valuable than originallyexpected.

But there are limits. The termination right can’t be used for works made for hire or grants made by will. There are timing restrictions, procedural requirements, and a narrow five-year window for termination, making this far from automatic. Creators must serve notice no earlier than 10 and no later than two years before the effective date. And the right doesn’t apply to all derivative works already made under the original grant.

In other words, it’s a maze. And it can take decades to effectuate.

What Coogler did was cut through that delay with an express termination clause, a contractual provision negotiated upfront to secure reversion of rights long before the law allows and without the procedural hurdles. It’s a radical act of foresight, and it redefines what ownership can look like for Black creators who are too often told to be grateful just for a seat at the table.

Ownership Beyond Control

Creative control is important. Final cut matters. First-dollar gross points matter. But what Coogler did was expand the definition of ownership to something broader: narrative sovereignty.

To own Sinners means that long after the box office receipts are counted and awards season buzz fades, the story and its cultural memory and intrinsic value remain tethered to the person who birthed it and the people he honored through it. It’s not just about profit. It’s about positioning. About legacy. About being able to shape how a story is used, where it is seen, how it’s preserved and what future generations can learn from it.

Ownership in this context is spiritual as much as it is legal. It’s a stand against the long history of Black stories being co-opted, distorted or monetized without consent.

It’s about refusing to be erased.

What This Means for the Industry and for Us

As someone who has spent her career studying and advocating for creator rights, particularly around copyright termination, I believe Coogler’s approach should be a model. Not every creator has the leverage of a two-time Oscar nominee, sure. But every creator deserves the chance to understand and negotiate for long-term control over their work.

This is especially urgent in the era of AI, streaming residual fights, and media consolidation. Stories—especially Black stories—cannot just be currency for studios. They are cultural capital.

The ability to own and control that capital is the gateway to generational wealth and influence.

Coogler didn’t make this move for all his films. He doesn’t plan to do it again. Still, in doing it for Sinners, he showed that sometimes, one project is enough to change the conversation.

And that’s why this moment matters.