As president, he encouraged companies such as Estée Lauder and Ford to place ads in the first magazine aimed at a large audience of Black women.

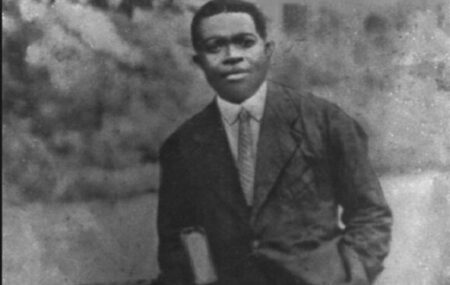

Clarence O. Smith, who helped convince doubtful advertisers about the importance of Black women as consumers and was one of the founders of Essence, the first widely distributed magazine aimed at Black women, passed away on April 21, 2025.

He was 92.

Smith, a resident of Yonkers, N.Y., died in a hospital after a brief illness, according to his niece Kimberly Fonville Boyd. She did not share any additional information.

Essence began as a monthly publication in May 1970, at a time when, despite significant advancements made by the Black community, there were still many negative and often harmful stereotypes surrounding Black women.

“We had to overcome this perception,” Edward Lewis, one of the four founders of the magazine, said in an interview. “Clarence suggested that we start telling the story of Black women as strivers.”

Smith, the president of the magazine and responsible for advertising and marketing, was the first to suggest the idea of the “Black Women’s Market”, a concept that highlighted the unique spending power and influence of Black women, which had often been ignored by mainstream advertisers. He persuaded reluctant companies to acknowledge that there were 12 million Black women in the U.S. who controlled a market worth over $30 billion.

The magazine aimed to focus on 4.2 million of the wealthier women in this group, specifically those aged 18 to 45 who lived in metropolitan cities, were educated, and had a growing amount of discretionary income. Smith’s innovative leadership transformed the advertising industry’s perspective on Black audiences, urging companies to not only invest but to do so with a genuine level of respect and understanding.

According to his colleagues, Smith was a confident and engaging speaker who was always prepared with thorough market research. But, he faced a clear challenge right from the start: the magazine’s first issue had only 13 pages of advertising and the following two issues had even fewer, with just five pages each.

Still, despite some ongoing difficulties, the publication began to improve under Smith’s tutelage. Circulation increased from 50,000 copies in the first run to over 1.1 million copies. The number of advertising pages also rose to more than 1,000 each year, attracting major companies like Estée Lauder, Johnson & Johnson and Pillsbury. By 2001, the cost for a full-page color ad jumped from $2,500 to $48,000.

“Clarence was a relentless champion for the leadership of Black women and the impact of our spending power that was ignored,” Susan L. Taylor, the magazine’s editor in chief from 1981 until 2000, said in an interview. “We have lost a mighty mind, but not a legacy. It lives on.”

The idea for the magazine started in November 1968 when a group of Black professionals, Lewis, Cecil Hollingsworth, and Jonathan Blount, met at a Wall Street conference focused on supporting African American entrepreneurs. Smith joined shortly after.

This period was marked by significant social turmoil in the U.S., including riots, the assassinations of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and escalating violence in the Vietnam War. Yet, it also presented new opportunities for Black-owned businesses amid the civil rights movement and the empowerment of Black women. Blount strongly advocated for a magazine aimed at Black women, inspired by his mother, who often questioned, “Why do I have to read magazines where I don’t see anyone who looks like me?”

Smith was the most successful and oldest of the original four partners, as noted in Lewis’s 2014 memoir, The Man From Essence: Creating a Magazine for Black Women. He was also the only partner with a car and successfully convinced major automotive companies like Toyota, General Motors and Ford to advertise in women’s magazines, which was rare at the time.

The inaugural cover of Essence featured a close-up of model Barbara Cheeseborough, celebrating her natural hair as a powerful symbol of both authenticity and glamour. Inside, there were photo essays on fashion and beauty, highlighting models of various skin tones. One article titled, Sensual Black Man, Do You Love Me? discussed Black men dating white women, while another highlighted women involved in the civil rights movement, including Rosa Parks and Kathleen Cleaver from the Black Panther Party.

Clarence O. Smith was born in the Bronx, New York, in 1933, to parents Clarence Smith and Millicent Frey (sometimes spelled Fry), and grew up in the Williamsbridge neighborhood of the borough. Before starting his own business, he served in the U.S. Army. Throughout his life, he received numerous accolades, including the A.G. Gaston Lifetime Achievement Award in 1997.

At Essence, he worked diligently to attract advertisers by putting ads on the first few pages and creating special issues focused on beauty and travel to connect with those specific industries. He also hired a sales team for advertising that was mostly made up of Black women, according to Marcia Ann Gillespie, who was the editor in chief of the publication from 1971 to 1980.

“The resistance of white businesses to associate with a Black women’s magazine was really intense,” Gillespie told The New York Times, and Mr. Smith, she added, “was always trying to find a way through and around and was relentless about it. Failure was not on his to-do list.”

While Smith was in charge, the brand continued to grow with new initiatives like the Essence Awards, Essence Television, and the hugely popular Essence Festival of Culture. The annual event in New Orleans during the July 4th weekend has become one of the most awaited events for the community, attracting about 500,000 people to the city each July.

“He was a futurist,” said Barbara Britton, a former vice president of advertising at Essence.

Smith worked at Essence for more than thirty years, mainly as president, where he concentrated on marketing and advertising. He is known for changing the brand’s approach to better serve Black audiences, especially Black women, and the positive effects of this decision are still evident today.

Mr. Lewis stated that Smith deserves high praise for emphasizing the importance of Black female consumers and shaping societal perceptions of Black women.

“He came across as authentic, really believing what he was selling, backed up by research,” Lewis said, remembering the magazine’s beginnings. “We were always prepared, because we knew that we were selling a market that no one wanted to be a part of.”

Clarence O. Smith is survived by his wife, Elaine, and their family.