There is something grotesquely elegant about watching a government reach back into the legal graveyard, pull out a law written to stop white men in hoods from terrorizing Black folks, dust it off, and then, without even a flicker of irony, use it to prosecute Black journalists for documenting racial injustice.

Seven people stand accused, among them former CNN anchor Don Lemon and three other Black journalists, not for violence, not for terror, but for being witnesses and documenting a protest that interrupted a worship service at a Minnesota church last month.

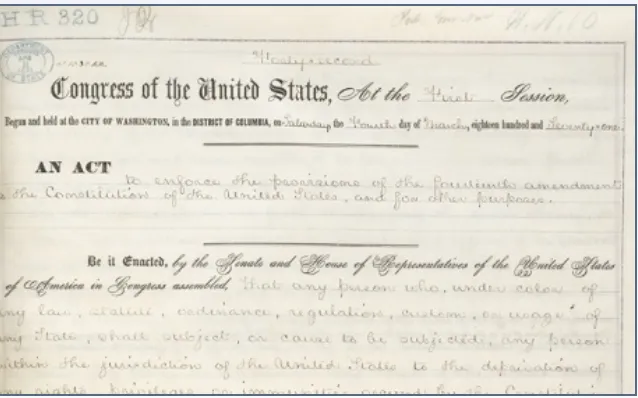

Federal prosecutors reached for two statutes to make it stick. One of them was the post–Civil War Conspiracy Against Rights law. That law was born in the blood-soaked aftermath of white vigilante terror. It was originally forged to crush the Ku Klux Klan. It was meant to protect Black people’s most basic constitutional existence.

The statute criminalizes intimidation meant to block people from exercising their rights. It was once aimed at men with ropes and torches. Now, with eerie procedural calm, it is being redirected toward Black journalists standing inside the long shadow of that very history.

You almost have to admire the choreography of it. The stillness. The bureaucratic confidence. The way power moves when it believes history belongs to it. Because this is not chaos. This is not confusion. This is not some accidental misapplication of a dusty statute nobody understands anymore. This is historical inversion done with surgical precision.

The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 came from a moment when Black freedom was so violently contested that Congress had to admit, out loud, that Southern states were unwilling or unable to protect Black citizens from organized white terror. The law gave the federal government teeth. It allowed prosecution when local authorities refused. It recognized that white supremacy was not just cultural. It was organized. It was political. It was lethal.

This law existed because of night riders, church burnings, political assassinations, mass lynchings, and coordinated campaigns to make Black citizenship functionally impossible. The Klan was not just a hate group. It was an insurgency. And Black people were the targets of a domestic terror campaign that local law enforcement often participated in or quietly endorsed.

And that history matters. Because this was never abstract legal theory. Thousands of Black people were murdered under the conditions that produced this law. Shot in front of their children. Dragged out of their homes. Lynched in public squares. Burned out of churches where they gathered because it was the only place they could breathe freely for a few hours.

Black churches were not random targets. They were political headquarters. Voter registration sites. Schools. Mutual aid networks. Survival infrastructure. When white mobs attacked churches, they weren’t just attacking buildings. They were attacking Black possibility. They were attacking Black futures.

The Ku Klux Klan Act was the federal government saying: enough. Enough pretending this was random violence. Enough pretending local authorities would fix it. Enough pretending this was anything other than organized racial warfare.

So when a law written in response to mass racial slaughter is used to prosecute Black journalists documenting racial injustice, this is not technical misapplication. This is moral category collapse.

Because what you are functionally doing is placing the work of witness into the same legal universe as organized racial terror. And that is where the grotesque part lives.

It lives in the quiet implication that documenting racial injustice can sit in the same moral and legal bucket as organized racial terror. It lives in the erasure of scale. Of context. Of blood. Of history. It lives in the way American institutions repeatedly flatten Black suffering into legal technicalities while expanding state power in the name of “order.”

Thousands of Black people died under the conditions that produced that law. Thousands. Not metaphor. Not rhetoric. Documented history. Mass graves. Unmarked burial sites. Families that never got bodies back. Generations raised on stories of who disappeared and why.

And now we are asked to accept a world where the democratic work of witness can be placed in rhetorical proximity to the vigilante tradition that law was designed to destroy.

Because once you collapse those categories, you don’t just criminalize witness. You minimize what white supremacist terror actually was. You shrink it into a “disturbance.” A “violation.” A technical breach of public order. And once terror becomes paperwork, history becomes easy to repeat.

The Klan was not a disorder problem. It was not a public nuisance. It was a domestic terror machine built to erase Black citizenship through fear, spectacle, and mass killing.

And now, more than 150 years later, that same legal architecture is being aimed in the opposite direction. Not at racial terror networks. Not at organized white nationalist violence. Not at the groups openly fantasizing about civil war and racial cleansing online. At Black journalists documenting racial injustice in real time. That is not irony. That is the goddamn strategy!

Because American racial power has never only been about domination. It has always been about narrative control. Who defines violence. Who defines disorder. Who defines threat. And one of the most reliable tools in that playbook is inversion.

Inversion is when civil rights law becomes “reverse discrimination.” Anti-lynching language becomes “law and order.” Voting rights enforcement becomes “election interference.” Anti-racist speech becomes “racial division.” And now, a Reconstruction-era anti-terror statute becomes a tool to criminalize Black documentation of racial injustice.

The pattern is brutally consistent. Civil rights protections are not just attacked. They are eventually repurposed. Not immediately. Not clumsily. But strategically. Once enough historical distance exists for the original bloodstains to be blurred, sanitized, or erased. And that erasure is not accidental.

Because you cannot weaponize civil rights law against Black people unless you first strip it of memory. You have to remove the smoke. The photographs. The testimonies. The written admission that white citizens once terrorized Black ones while state governments stood aside.

Once you erase that, you can do anything.

You can prosecute protest. Criminalize documentation. Collapse the difference between terror and resistance. Make surveillance look like safety. Make state power look like stability. Make historical memory look like extremism.

And this is not just about one case. This is about precedent. About signaling. About reminding anyone paying attention that civil rights enforcement tools are now available for political repurposing.

Because the most dangerous power is not the power that announces itself. It is the power that says, “We are simply enforcing the law.” The power that hides inside technical legality while doing morally unrecognizable things. That is the predatory calm of this moment.

If this feels surreal, it is because you are watching historical time fold in on itself. Reconstruction never ended. It adapted. It bureaucratized. It traded robes for suits. It traded crosses for court filings. But the underlying question never changed. Who defines justice. Who defines violence. Who defines disorder.

Because if documenting racial injustice can be reframed as civil rights violation, then the moral architecture flips. The oppressor becomes the victim. The witness becomes the criminal. The state becomes the protector. And history becomes whatever power says it is in that moment. And history is very clear about where that road leads.

There is nothing accidental about this moment. There is nothing sloppy about it. There is something terrifyingly polished about it. And that is exactly why people should be paying attention.

Because the moment a nation becomes comfortable using anti-terror law against the descendants of the people it was originally written to protect, you are no longer talking about legal interpretation. That is not jurisprudence. That is ritualized forgetting. That is a country reaching into its own archive, ripping out the pages stained with Black blood, and pretending the remaining text was always meant for someone else.

Thanks for reading. If this piece resonated with you, then please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Paid subscriptions help keep my Substack unfiltered and ad free. They also help me raise money for HBCU journalism students who need laptops, DSLR cameras, tripods, mics, lights, software, travel funds for conferences and reporting trips, and food from our pantry. You can also follow me on Facebook!

We appreciate you!