While many of us are headed for beaches in search of some well-deserved relaxation and sunshine this season, you might want to consider a visit to one of the historic Black beaches and resorts that have significantly influenced our culture, community and enjoyment over the years.

Of course, we can choose to visit any beach we like, but that was not the case for our ancestors. During the Jim Crow era, they were barred from using most public beaches, too. But in reaction to being left out, Black entrepreneurs and families built their own beach resorts and neighborhoods where they could enjoy their culture in a safe space.

These sandy retreats not only offered a place to swim and just be, they afforded Black folk the freedom to enjoy a life filled with opportunities without facing a tidal wave of white resistance and discrimination.

We’ve put together a list of some of these treasured destinations where you can kick back and have a little fun, while also celebrating the Black Americans who overcame the challenges of racism to find their joy and freedoms.

Here are their stories.

Atlantic Beach, South Carolina

When segregation barred Black families from enjoying various beaches along the East Coast, Black entrepreneur George W. Tyson dreamed of establishing a beach community for his people. In 1934, he created Atlantic Beach by purchasing 42 acres of land in Horry County, South Carolina, where he initially constructed a nightclub for Black Americans who were excluded from whites-only clubs in Myrtle Beach.

He then invited other Black citizens to invest with him, and by March 1936, Black entrepreneurs had purchased 10 plots of land which led Tyson to buy even more acreage to keep up with the growing demand. The beach community, often called the “Black Pearl,” quickly thrived with restaurants, homes, entertainment spots, banks and other businesses.

In the early 1940s, Tyson sold the area to a group of Black professionals known as the Atlantic Beach Company, which continued to develop the land through the 1950s. Residents of Atlantic Beach enjoyed amusement park rides, arcade games and a movie theater. Renowned musicians such as James Brown and Fats Domino unwound in the community after their shows at clubs in Myrtle Beach. An outdoor pavilion featured performances by artists like Tina Turner and Ray Charles.

The local culture was also enhanced by influences from West and Central Africa, particularly evident in the food, music and arts. This transformation occurred as the descendants of the Gullah Geechee people made this region their home.

However, in October 1954, Atlantic Beach suffered significant damage when Hurricane Hazel, a Category 4 storm, tore through the community, destroying wooden buildings and the pier. During the 1960s, as desegregation laws took effect, tourists began to explore alternative vacation destinations.

Despite these challenges, Atlantic Beach showed resilience. In 1966, it became an incorporated city, leading to the creation of a fire department and a city council.

Today, the Black Pearl is one of the few remaining all-Black beach communities in the country.

Biloxi Beach, Mississippi

Along the Gulf Coast, beaches emerged as sites for advocating social justice. In 1955, Dr. Gilbert Mason, a Black physician, relocated to Biloxi, Mississippi. Having traveled widely and experienced diverse environments, he was disheartened by segregation in public spaces and the various civil rights challenges of the era. To combat these injustices, he organized a series of peaceful local protests known as “wade-in” demonstrations, where African Americans walked through shallow waters in the Gulf of Mexico.

The first wade-in at Biloxi Beach took place on May 14, 1959. Police ordered the protesters to leave the water, citing state segregation laws. Later that year, after local citizens requested that county officials allow Black Americans access to the beach, a supervisor suggested they might be okay with a separate section. Mason refused this offer.

On April 17, 1960, Mason was arrested during a second wade-in, which angered the Black community in Biloxi with many vowing to support him in future protests. A week later, 125 Black citizens of all ages joined Mason for what became known as Bloody Wade-In Day.

White supremacists counter-protested by throwing rocks at the Black beachgoers and firing guns into the air. The police did not intervene which led to many injuries. Eight Black men and two white men were shot, but Mason was the only protester arrested and later convicted of disturbing the peace.

Despite lawsuits from local civil rights leaders and the U.S. Justice Department, county officials kept the beaches segregated. On June 23, 1963, shortly after a white supremacist killed NAACP leader Medgar Evers, Black Americans held their final wade-in. Over 2,000 white residents attacked many Black demonstrators and damaged police cars, and the majority of the arrests that day were of Black individuals.

Before his murder, Evers wrote to Mason, saying, “If we are to receive a beating, let’s receive it because we have done something, not because we have done nothing.”

About five years after the Civil Rights Act was passed, Biloxi Beach was finally integrated. While justice took time, the wade-ins showed the strength of Black Mississippians, and Mason was later recognized for his leadership during the 50th anniversary of the protests.

Chicken Bone Beach, New Jersey

Before 1900, Black and white visitors shared Missouri Avenue Beach in Atlantic City, but this changed when hotels began catering to Southern white segregationists. To satisfy their new guests, business owners started to push African Americans to a different area, which later became known as Chicken Bone Beach.

Black families and friends turned this segregated spot into a joyful retreat, bringing picnic baskets filled with fried chicken and enjoying the sand and sun with beach balls and stylish swimwear. After eating, they would bury the chicken bones in the sand, which is how the beach got its name.

In the 1940s, Black celebrities, entertainers, and civil rights activists contributed to the area’s growing popularity. Notable visitors included Sammy Davis Jr., comedian Jackie “Moms” Mabley, and boxing champion Sugar Ray Robinson. In 1956, photographer John Mosley captured a picture of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. taking a casual stroll along the beach.

The all-Black beach faded away after the 1964 Civil Rights Act ended segregation. Since then, local leaders and musicians have honored the area in different ways. In 1997, the city declared the beach a historic landmark and today, the Chicken Bone Beach Historical Foundation works to keep the cultural importance of the area alive through jazz music.

Highland Beach, Maryland

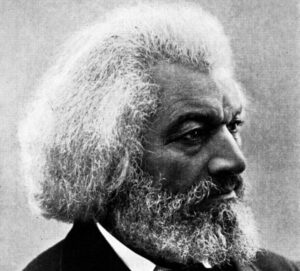

Highland Beach, located on the Chesapeake Bay, is the oldest major resort town for Black people in the U.S. It was founded in 1893 by Charles and Laura Douglass along the western shore. Charles Douglass was the son of abolitionist and civil rights leader Frederick Douglass.

Major Charles Douglass was notable in his own right. He was a retired officer from the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry, the first Black regiment to serve during the Civil War, and he also dedicated many years of service to the Treasury Department.

Situated in Anne Arundel County, about 35 miles east of Washington, D.C., and a few miles south of Annapolis, Maryland, Highland Beach became the first summer resort community owned by African Americans in the country. It was created in response to racial discrimination when Major Douglass and his wife were turned away from a restaurant at The Bay Ridge Resort in 1890 because they were Black. As a result, he entered the real estate market and began buying beachfront land just south of Bay Ridge. He purchased over 40 acres for $5,000 and started developing it as a summer resort by selling lots to family and friends.

Douglass also built a large family summer home called Twin Oaks. This house was meant primarily for his father to retire in, but it soon became a popular spot for many influential African Americans from the Washington-Baltimore area who came to visit Frederick Douglass. Although Frederick Douglass passed away before he could live there permanently, the community of Highland Beach quickly became a favorite destination for many prominent Black figures, including Paul Robeson, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, Langston Hughes, Robert Weaver and Alex Haley.

Charles Douglass believed his biggest achievement in creating Highland Beach was finding ways around property laws that prevented Black people and other minorities from buying real estate in the area. Initially intended as a summer getaway, by 1915, Highland Beach had developed into a year-round community, with many homes still owned by the descendants of the original families.

Oak Bluffs, Martha’s Vineyard

Martha’s Vineyard is predominantly home to white residents, yet Oak Bluffs, one of its vibrant towns, boasts a significant history as a summer getaway for African Americans. In the early 1900s, it became a favored destination for middle-class Black families seeking relief from segregation and discrimination, having attracted prominent historical figures such as Maya Angelou and Paul Robeson.

In 1912, Charles Shearer, the son of an enslaved woman and her enslaver, established the first Black-owned inn in Oak Bluffs, as Black travelers had very few safe accommodations for their vacations. The Shearer Inn quickly gained popularity, particularly during the Harlem Renaissance and other periods of Black economic progress. Each summer, the area drew the Black elite and business owners who came to enjoy Inkwell Beach, affectionately known as “The Inkwell,” where they celebrated their own version of summer enjoyment.

The origin of the name “The Inkwell” remains a topic of debate. Some believe it was created by Black visitors who, observing the beach from nearby sidewalks, noted the water filled with Black people, resembling an inkwell. Others say that it was initially a derogatory term used by white residents to segregate the beach. However, Black visitors later reclaimed the term, transforming it from a negative connotation into a positive one.