On September 10, 1779, Nathaniel Wells was born on the island of St. Kitts in the Caribbean.

Nathaniel Wells was the son of William Wells, a wealthy Welsh plantation and enslaver, and an enslaved Black woman whose name has been lost to history. In the rigidly stratified Caribbean of the late 18th century, Nathaniel’s mixed heritage might have consigned him to a life of bondage. Instead, his father acknowledged him and ensured he was educated and financially supported.

This recognition, rare in its time, set Nathaniel on a path unlike almost any other man of African descent in the British Empire. Inheriting considerable wealth from his father, Wells crossed the Atlantic and settled in Monmouthshire, Wales, where he invested in land and property. He purchased the grand Piercefield Estate near Chepstow, a mansion and grounds that became a visible symbol of his prominence.

Despite his race, Wells was embraced by many in the local elite. His fortune spoke volumes in a society where wealth could sometimes blur the lines of prejudice. Yet his success was always shadowed by its origins: the sugar trade and slavery.

In 1818, Nathaniel Wells made history when he was appointed High Sheriff of Monmouthshire, becoming the first Black man to hold the title in Britain. The position, which carried both prestige and responsibility, placed him firmly within the ruling gentry.

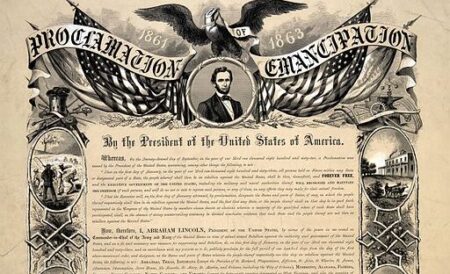

At a time when Britain’s colonies were still deeply entangled in slavery, Wells’ appointment was groundbreaking. It challenged prevailing assumptions about race and power, though it did not dismantle the system that had enabled his rise.

Later, as a plantation owner, he resisted emancipation, clinging to slavery even after it was outlawed in the British Empire. When Parliament compensated slaveholders in 1837, Wells, like many of his peers, accepted payment for releasing enslaved people, treating human lives as mere property to be bargained over. In declining health, he moved to Bath in 1850 to “take the waters,” a popular therapeutic practice of the era. At his death in 1852, Wells left behind immense wealth and a sprawling family.

Wells was a man of paradox. While he was a pioneering Black figure in Britain, he also inherited and maintained plantations in the Caribbean, complete with enslaved laborers. This duality makes his legacy difficult to categorize neatly, as he was undoubtedly a mark of racial progress, but he was also complicit in the very system which oppressed millions of people of African descent.