The Datcher Family name has become synonymous with perseverance, stewardship, and quiet leadership in the Black farming communities of Alabama. For generations, the Datchers have coaxed life from the red clay soil, turning acres of hardship into a legacy of hope and opportunity.

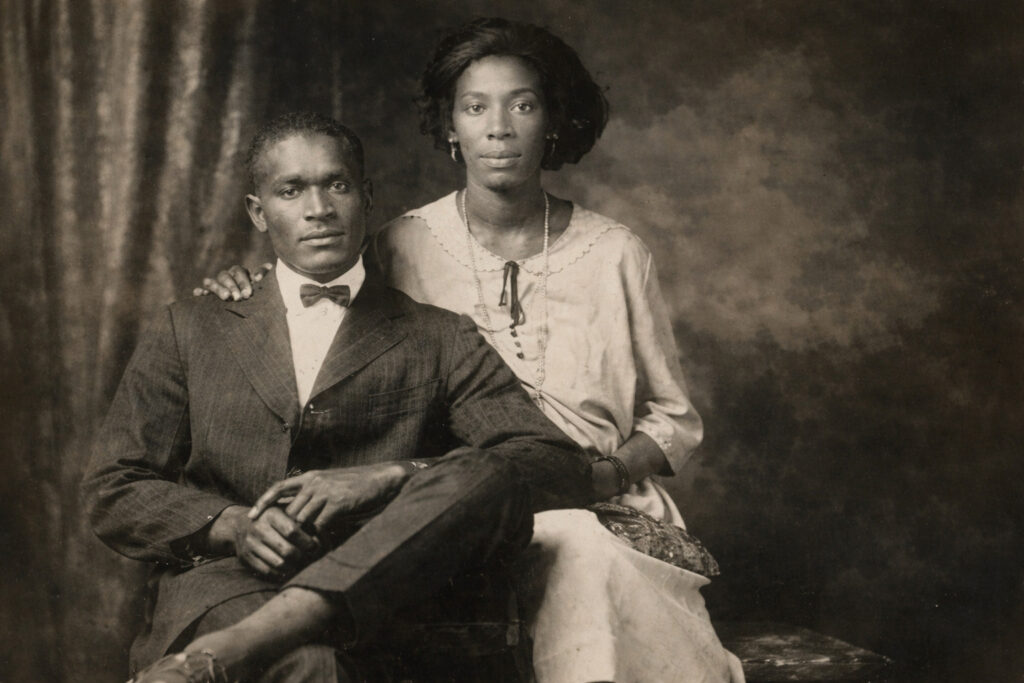

Family stories trace the first Datcher farmers to the 1800s, when newly freed ancestors scraped together enough money to purchase a few rocky acres in Harpersville, Shelby County, Alabama. The land was exhausted and unforgiving, but it represented something priceless: ownership and the promise that their children would never again be treated as property.

Those first years demanded everything. By mid-century, a new generation of Datchers emerged as quiet innovators. They experimented with soil conservation methods, rotated crops to restore fertility and introduced new varieties better suited to Alabama’s heat and drought. When federal programs often bypassed Black farmers, the family shared what they learned informally over church suppers, at fence lines and at the local feed store.

Education became a cornerstone of the Datcher legacy. Children were expected to excel in school and understand the science behind what their grandparents had learned by feel. Some studied agriculture and business, returning home with degrees to modernize record-keeping, explore cooperative marketing and navigate loans and grants that earlier generations had been denied.

Working sunup to sundown, the early Datchers planted cotton and corn alongside kitchen gardens that stretched behind the modest farmhouse. They bartered eggs and vegetables, repaired their own tools and taught each child that every fence post and furrow carried the weight of family sacrifice.

Even as land loss eroded countless Black-owned farms across the South, the Datchers fought to hold on, meticulously protecting deeds, paying taxes on time and ensuring each transition of ownership was secure. Their acreage became not just a workplace but a living archive of African American rural history.

As Jim Crow tightened its grip on the South, many neighbors left for factory work up North. The Datchers stayed. They diversified their crops, adding peanuts, sweet potatoes and livestock to hedge against bad seasons and unstable prices. In the process, they created a model of small-scale resilience that would guide the family for decades.

Today, younger Datcher descendants blend tradition with innovation through farm-to-table partnerships, community-supported agriculture, and workshops for local youth. Through them, the Alabama soil still carries the imprint of generations who believed that working the land could also work a quiet revolution.