One could successfully argue that no other small town has contributed so much to advancing human freedom in the United States during the 20th century as Mound Bayou, Mississippi.

Nestled in the heart of the Delta, this dynamic community emerged as a symbol of hope and strength, nurturing the emergence of prominent leaders like Medgar Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer and Rosa Parks—powerful individuals who might have otherwise remained invisible to history. The town’s dedication to social justice and spirit of activism provided a fertile ground for forward-thinking ideas to flourish and for movements to gain momentum, demonstrating that even the smallest communities can play monumental roles in shaping the course of a nation.

In an era marked by viscous systemic oppression and racial segregation, the town became a sanctuary where Black entrepreneurs could launch businesses, educators could inspire learning and families could build futures free from the constraints imposed by a prejudiced society. This sense of empowerment not only transformed the lives of those within the community but also rippled outwards, influencing the broader civil rights movement.

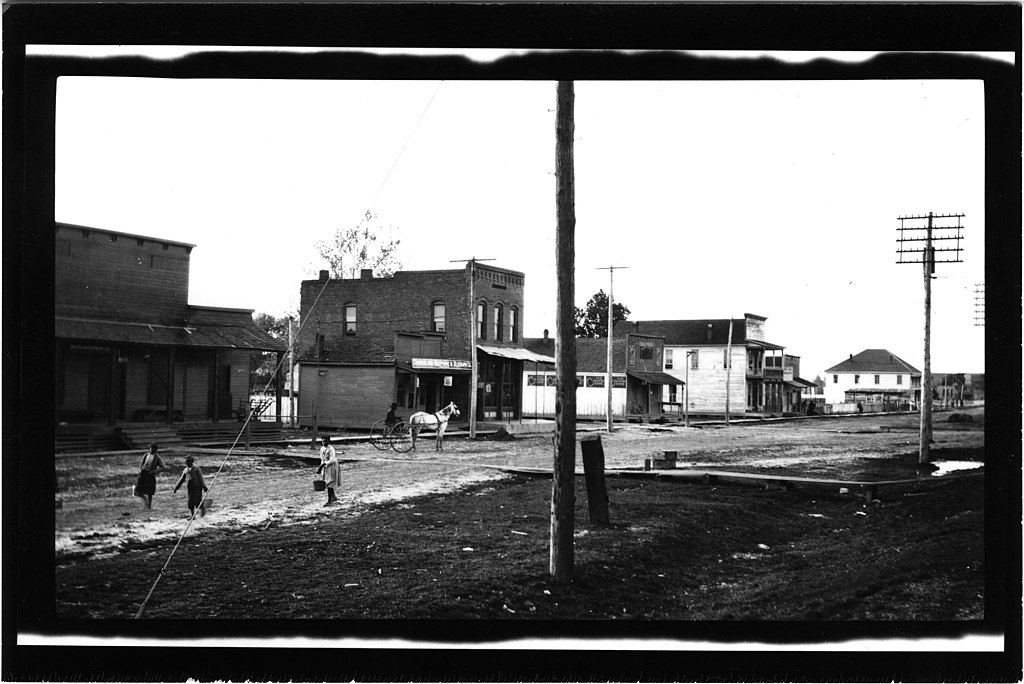

The town, established in 1887 by cousins Isaiah T. Montgomery and Benjamin T. Green, stands in the face of a tumultuous history. Both men were formerly enslaved by Joseph Davis, the brother of Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president. The name Mound Bayou comes from a significant prehistoric Indian mound, located at the meeting point of two bayous, representing the deep-rooted heritage and cultural importance of the area.

For decades, Mound Bayou blossomed into a vibrant all-Black community. It was the only place in Mississippi where being Black could mean being prosperous. The town offered a rare opportunity for Black citizens to exercise their rights fully—enjoying free speech, assembling peacefully, voting and even holding public office. Montgomery frequently emphasized the importance of this freedom, recalling how he and Green transformed a wild, uninhabited area into a thriving community that championed self-expression and economic growth. Their vision laid the groundwork that made Mound Bayou not just a place to live, but a mark of what could be achieved through unity and determination.

Montgomery and Green understood that for Mound Bayou to succeed, it needed a political climate conducive to business development and the rule of law, and they inspired many African Americans to keep a close eye on what was happening in the town. They viewed this as a practical illustration of Booker T. Washington’s belief, which he also passionately supported, that achieving political rights necessitated gradual economic empowerment.

By the 1910s, Mound Bayou had a population of 2000, with 13 stores, numerous small businesses, a sawmill, three cotton mills, the largest Black-owned bank in Mississippi and 10 churches. It also had a privately-operated high school with two hundred students, a rarity for African Americans nationwide. The only institution run by white individuals was the local Carnegie Library, which was established after Booker T. Washington personally requested support from Andrew Carnegie. Various Black organizations from across the state frequently held their meetings in Mound Bayou, where they felt secure from racist curfews and other police mistreatment.

Even as Jim Crow laws were tightening their grip on the South, African Americans across the country celebrated Mound Bayou as a shining example of self-determination and financial autonomy. It demonstrated what could be achieved even in the face of oppression. Prominent whites began to pay attention as well. In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt took notice and made a special visit during his travels to praise it as “the jewel of the Delta” and an “object lesson full of hope for the colored people and therefore full of hope for the white people, too.” His words emphasized the town’s significance not just for African Americans, but for society as a whole. Four years later, Booker T. Washington addressed a large crowd, praising Mound Bayou as a source of inspiration, where African Americans could witness the achievements of their peers and learn vital skills for civic engagement.

After World War I, the town faced falling cotton prices, destructive fires and violent conflicts that put the town’s survival at risk. Mayor Benjamin A. Green, the son of Benjamin T. Green, was pivotal in keeping the community afloat during these tough times. He passionately promoted Mound Bayou’s historical importance as a source of inspiration, and his strong diplomatic abilities, bolstered by his Harvard education, were critical in protecting it from threats posed by hostile outsiders and in advancing peace within the community.

One key aspect of Green’s long leadership was his informal approach to addressing crime and resolving conflicts through negotiation and consensus. A local resident remarked in the 1920s that the only real trouble in the town stemmed from a few poor whites who came for a Fourth of July picnic and ended up getting drunk. The town was so secure that it closed its only jail in 1929, considering it no longer necessary.

In 1942, Dr. T.R.M. Howard arrived as the chief surgeon of the new all-Black Taborian Hospital, bringing new energy to the town and its founding ideals. The hospital was created by P.M. Smith, leader of the Knights and Daughters of Tabor, a mutual aid organization. The hospital offered affordable services, with annual dues of $8.40 (equivalent to about $158 today) covering thirty-one days of hospital care, including surgeries. During the hospital’s opening ceremony, Mayor Green proudly highlighted the achievements of “this law-abiding, God-fearing, and jail-less city, an All-Negro city if you please, where you can see freedom and safety like nowhere else in the mid-South.”

The appeal of the hospital led to a quick increase in the membership of the Knights and Daughters of Tabor, reaching nearly fifty thousand. Most members were women, many of whom worked as sharecroppers and farm laborers. Despite coming from poor backgrounds, they managed to meet their social welfare needs by pooling their resources without any help from the government.

Using the hospital as a starting point, Howard created a one-thousand-acre farm, the first swimming pool for African Americans in the state, a home construction business, a small zoo, a nice restaurant, and a community entertainment center that drew visitors from afar. He encouraged African Americans to remain in Mississippi and work to improve their situation instead of moving to the North, saying that “there is nothing wrong with Mississippi that hard work, a better education system, true practice of Jesus Christ’s teachings, and real democracy can’t fix.” He wanted this “little town to symbolize hope for many African Americans, and he hoped it would inspire even more.”

Mound Bayou, once a thriving haven for African Americans, has seen its vibrancy fade through the Great Migration and desegregation, leaving it a shadow of its former self. But today, despite a sharp decline in population and economic challenges, the spirit of the early pioneers still thrives within the community.

While Mound Bayou may no longer shine as the “Jewel of the Delta” anymore, it remains a lively community and a noteworthy site of African American legacy, as seen in the Mound Bayou Museum of African American Culture and Heritage.

Local leaders understand the importance of preserving this historic town, not just as a reflection of the past, but also as a reminder of the ongoing pursuit of equality and justice.