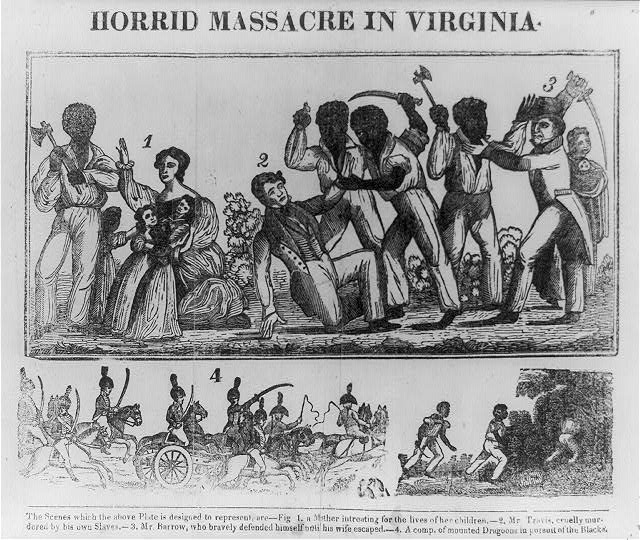

On August 21, 1831, Nat Turner initiated the deadliest slave revolt in the history of the United States. In Southampton County, Virginia, Turner and his fellow insurgents rose against the institution of slavery.

Armed with weapons such as axes and knives, Turner and his group of both enslaved and free Black people launched their attack under the cover of darkness, Turner and his group of both enslaved and free Black people claimed the lives of 55 white individuals, driven by Turner’s belief in the divine imperative to liberate his people from bondage, sending shockwaves throughout Southern society.

However, in less than 24 hourswhite militias and armed civilians engaged the rebels at James Parker’s farm and quickly quashed the uprising’s momentum.

The response from white Virginians was swift and severe. In the chaotic aftermath, dozens of Black individuals, many completely uninvolved in the rebellion, both enslaved and free, were killed extrajudicially. Eventually, local authorities attempted to restrain this violence by instituting formal trials, a process partly motivated by the economic interests of slaveholders who could receive state compensation for executed enslaved people.

Formal trials commenced on August 31, 1831. Within a month, 30 enslaved people and one free Black man were sentenced to death; nineteen of these sentences were carried out, while 12 individuals had their sentences commuted by Governor John Floyd.

Turner himself eluded capture for several weeks, hiding in the forests near the site of the insurrection. He was eventually caught and turned over to the authorities on October 30. He would go on to tell his version of the event to Thomas R. Gray, which was later published as The Confessions of Nat Turner, released ahead of Turner’s execution on November 11, 1831.

Fear of further uprisings rocked the slaveholding class, and lawmakers in Virginia considered the prospect of emancipation. Notably, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, Thomas Jefferson’s grandson, presented a plan for incremental liberation, though it ultimately failed. In response, Southern states strengthened legal limitations on the movement, education and assembly of enslaved people.